Hannah Arendt’s “On Lying and Politics” is a collection of two seminal essays that explore the complex relationship between truth, lies, and political power. The book, published in 2022, includes “Truth and Politics” (1967) and “Lying in Politics” (1971), along with a new introduction by David Bromwich.

Key Themes of “On Lying and Politics”

The nature of political lies

Arendt argues that the phenomenon of lying in politics is not new, and that truthfulness has never been considered a political virtue. She posits that lies have long been regarded as justifiable tools in political dealings, reflecting a deep-seated tension between truth and politics. However, Arendt also warns that excessive lying by political classes can lead to totalitarianism, where reality becomes entirely fictional.

Types of truth

Arendt distinguishes between two types of truth: factual and rational. She argues that factual truth is more vulnerable to political manipulation, as it is not self-evident and can be challenged like opinions. Rational truth, on the other hand, is more resilient as it can be reproduced through logical reasoning. Others can more easily verify on their own whether a rational truth checks out, whereas they cannot as easily go fact-finding — particularly about far-flung things that happen well outside their ken.

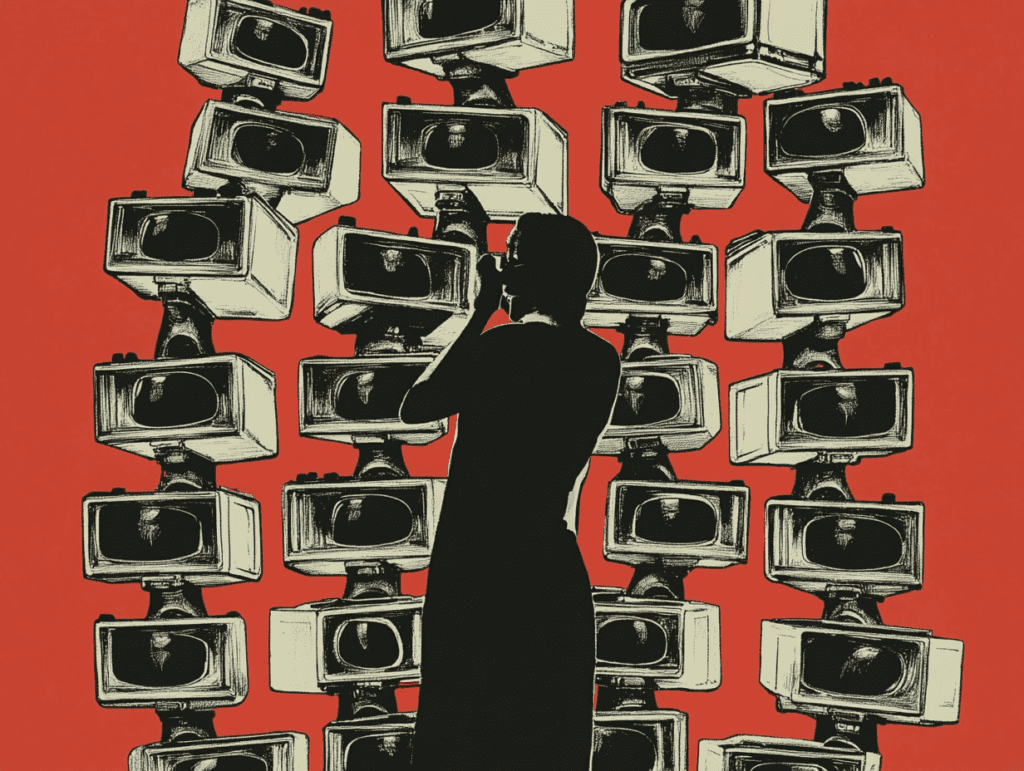

The impact of lies on democracy

Arendt explores how organized lying can tear apart our shared sense of reality, replacing it with a fantasy world of manipulated evidence and doctored documents. She argues that in a democracy, honest disclosure is crucial as it is the self-understanding of the people that sustains the government. This aligns with the idea that totalitarian governments can warp even the language itself, a la George Orwell’s Newspeak language in the classic novel 1984.

A Tale of Two Essays

“Truth and Politics” (1967)

In this essay, Arendt examines the affinity between lying and politics. She emphasizes that the survival of factual truth depends on credible witnesses and an informed citizenry. The essay explores how organized lying can degrade facts into mere opinions, potentially leading liars to believe their own fabrications in a self-deluding system of circular logic.

“Lying in Politics” (1971)

Written in response to the release of the Pentagon Papers, this essay applies Arendt’s insights to American policy in Southeast Asia. She argues that the Vietnam War and the official lies used to justify it were primarily exercises in image-making, more concerned with displaying American power than achieving strategic objectives.

Arendt’s perspective on political lying

Arendt views lying as a deliberate denial of factual truth, interconnected with the ability to act and rooted in imagination. She argues that while individual lies might succeed, lying on principle ultimately becomes counterproductive as it forces the audience to disregard the distinction between truth and falsehood.

Contemporary relevance

Arendt’s work remains highly relevant today, perhaps even more so than when it was written. Her analysis of how lies can undermine the public’s sense of reality and the dangers of political self-deception resonates strongly in our current political climate of disinformation, manipulation, and radicalization.

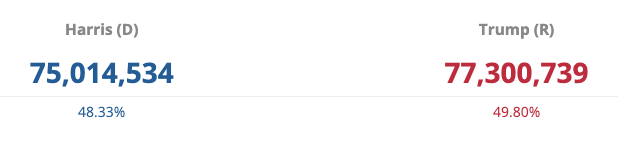

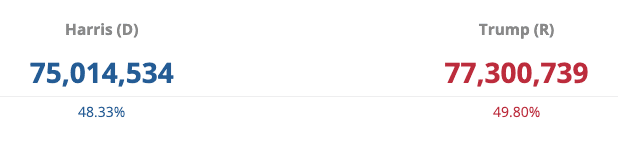

Today, even natural disasters are politicized — spawning dangerous conspiracy theories that do actual harm by discouraging people from getting help, among other tragedies of ignorance. And the right-wing is almost zealous about retconning the history trail and shoving things down the memory hole, including “rebranding” the J6 insurrection as a “day of love” and imagining away Donald Trump’s 34 felony counts.

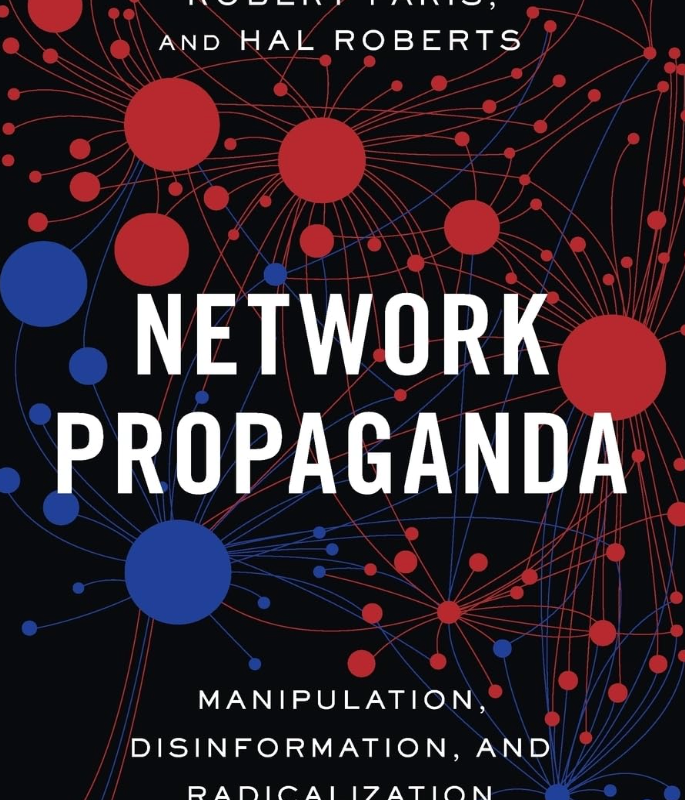

Not to mention, the incredible contribution from Big Tech — whose tech bros have seen to it that political technology, and the study of professional manipulation, is alive and well. It’s been in the zeitgeist for a couple of decades now, and is now being accelerated — by the ascendancy of AI, Elon Musk, and the Silicon Valley branch of the right-wing wealth cult (Biden called it the tech-industrial complex).

“On Lying and Politics” feels fresh today

Arendt’s “On Lying and Politics” provides a nuanced exploration — and a long-term view — of the role of truth and lies in political life. While acknowledging that lying has always been part of politics, Arendt warns of the dangers of excessive and systematic lying, particularly in democratic societies.

Her work continues to offer valuable insights into the nature of political deception and its impact on public life and democratic institutions. We would be wise to hear her warnings and reflect deeply on her insights, as someone who lived through the Nazi regime and devoted the remainder of her life’s work to analyzing what had happened and warning others. The similarities to our current times are disturbing and alarming — arm yourself with as much information as you can.