Critical thinking is a disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. It involves questioning ideas and assumptions rather than accepting them at face value.

It requires curiosity, skepticism, and humility to acknowledge the limitations of one’s knowledge and understanding. Critical thinking enables individuals to make reasoned judgments that are logical and well-thought-out. It is a foundational skill for problem solving and decision making in a wide range of contexts, and it empowers individuals to act more wisely and responsibly in their personal, professional, and civic lives — as well as to better evaluate the claims of experts.

Think Better with Mental Models

Mental models are a key component of critical thinking. They are a kind of strategic building block we can use to make sense of the world around us.

Some are formal mathematical proofs, some are scientific theories, and along the other end of the continuum are models more akin to metaphors or ancient wisdoms that still hold true today — they’ve been time tested and still hold explanatory value in helping us understand new (and new to us) phenomena.

Legendary investor Charlie Munger referred to mental models as the secret sauce of successful decision-making. Mastering multiple of the below models “is the best thing you can do,” he once said.

Mental Models for Improving Your Critical Thinking

Models are often extensible, and can apply to other systems in addition to their systems of origin. In fact, the most powerful models seem to show up again and again, across different disciplines and in a wide variety of contexts. They’re a bit like a mental image of how something works, that helps us predict what will happen next or explain how something works to others.

Also, multiple models can often be applied to the same systems — in order to describe different parts of that system, or account for different contexts, use cases, or configurations of the same process. Mental models aren’t like multiple-choice tests, where only one answer is correct — typically, a set of different models may have value in giving us a sense of how something works or how an ecosystem behaves.

See here for the set of Top Models to start with.

Then, follow up with the unabridged and upcoming collection I will continuously update and curate over time:

- 4GW — 4Fourth Generation Warfare (4GW) refers to a form of conflict characterized by decentralized, non-state actors using unconventional tactics, such as guerrilla warfare, terrorism, and psychological operations, to undermine stronger traditional military forces. It often blurs the lines between combatants and civilians and emphasizes ideological, cultural, and media-based strategies to achieve political goals.

- Absolute value — In math, the distance of a number from zero on the number line, without considering the direction; it is always a non-negative number.

- Action bias — The tendency to prefer action over inaction, often driven by the emotional discomfort of feeling unproductive or the desire to appear decisive.

- Adjustment heuristic — A cognitive shortcut or bias where people estimate a value based on an initial starting point (anchor) and then make adjustments from that point to reach their final estimate, often leading to systematic errors in judgment.

- Agency capitalism — Alfred Rappaport’s agency capitalism theory, as outlined in “Creating Shareholder Value,” addresses the conflict between corporate managers (agents) and shareholders (principals) by advocating for the alignment of managerial incentives with shareholder interests. Rappaport emphasizes that the primary goal of a corporation should be to maximize shareholder value through strategic planning, effective capital allocation, and performance metrics like economic value added (EVA) rather than traditional accounting measures. By promoting strong corporate governance, transparent communication, and incentive-based compensation, Rappaport’s theory aims to mitigate the agency problem and ensure long-term value creation for shareholders.

- Agile vs. Waterfall — 2 distinct methodologies or philosophies of project and product management: agile is more iterative and collaborative, while waterfall is more sequential and linear in nature.

- Alchemy — The medieval progenitor of the science of chemistry, based on the misguided ambition of transforming matter — often specifically the transmuting of base metals into gold.

- Alternative Available Principle — The alternative available principle states that your negotiating power or pricing leverage depends entirely on how attractive your customer’s next-best option is—if they have a great alternative, you have weak leverage; if their alternatives are poor or nonexistent, you have strong leverage. Essentially, you can only capture value up to the point where switching to their best alternative becomes more appealing than continuing to deal with you.

- Ambiguity aversion — A preference for known risks over unknown risks.

- Analysis paralysis — The inability to make a decision because of over-thinking a problem, and becoming paralized by too much data and/or too many options to consider.

- Anarcho-capitalism — A political philosophy that claims governments are not needed, only private property rights.

- Anchoring effect — A cognitive bias where individuals rely too heavily on an initial piece of information (the “anchor”) when making decisions, even if it’s unrelated to the decision at hand.

- Anecdotal vs. statistical — Anecdotal evidence refers to personal stories or isolated examples that people often use to illustrate or support a point, whereas statistical evidence involves data and analysis from systematic research or studies, providing a broader, more generalizable understanding of a topic.

- Anocracy — A hybrid form of government blending democracy and dictatorship, in which some public participation is available, but not a full set of mechanisms for addressing civic grievances.

- Antifragility — Systems that benefit from fragility; achieves growth from volatility (Nassim Taleb).

- Arete — Excellence in moral virtue (ancient Greece).

- Arrow of time — The concept that time seems to flow in a single direction from the past to the future, characterized by the growth of entropy and the irreversible progression of physical processes.

- Arrow’s Theorem — Social-choice paradox showing the flaws of ranked voting systems.

- Arrested development — A stoppage of physical or psychological development, leading to an individual’s failure to achieve the milestones typically associated with a certain life stage, often due to psychological or environmental factors.

- Asch Experiments — Set of experiments showing that people can be social pressured into conforming a lot more easily and often than we might imagine.

- Askers vs. Guessers — Cultural metaphor sorting people into two buckets: Askers will simply ask for anything they like, expecting that sometimes the answer will be “No.” Guessers will rarely ask for something if they feel the answer might be No, and dislike being put in the position of saying No to an Asker.

- Asymptote — A curve that approaches the value of a line on a graph but never reaches it.

- Attention restoration theory — concept that nature replenishes our ability to concentrate and pay attention.

- Austrian School economics — An outdated school of economic thought that emphasizes the spontaneous organizing power of the price mechanism and holds that the complexity of subjective human choices makes mathematical modeling of the evolving market practically impossible.

- Authoritarian personality — A psychological concept describing individuals who exhibit a strong adherence to conformity, authority, and rigid structure, often leading to prejudice and an intolerance for ambiguity.

- Availability heuristic — A mental shortcut that relies on immediate examples that come to a person’s mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method, or decision, leading to a biased judgment based on recent information or personal experience.

- Avogadro’s Number — 6.022 X 10^23, the number of atoms or molecules in a mole, the base unit of measurement for an equivalent amount of a substance in chemistry.

- Banality of evil — The concept of the “banality of evil,” coined by philosopher Hannah Arendt, describes the phenomenon where ordinary individuals commit heinous acts without evil intent, often through a lack of critical thinking and a blind adherence to orders or norms. This idea emerged from Arendt’s observations during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi bureaucrat who facilitated the Holocaust by following orders and bureaucratic processes without question.

- Banana republic — A banana republic is a politically unstable country with an economy dependent on the export of a single resource, often controlled by foreign corporations. This term typically implies corruption, exploitation, and a lack of democratic governance.

- Bandwagon effect — A psychological phenomenon where people adopt beliefs or behaviors simply because others are doing so, often driven by the desire to conform or fit in.

- Basic Goodness — Shambhala Buddhist concept of basic human worthiness in people of all faiths, colors, and varieties.

- Bayes’ Theorem — Bayes’ Theorem is a fundamental concept in probability theory that allows you to update the probability of a hypothesis as more evidence or information becomes available.

- Begging the question — A logical fallacy in which an argument’s premise assumes the truth of the conclusion instead of providing evidence for it. Essentially, the argument circles back on itself without proving anything, often rephrasing the conclusion as part of the proof.

- Bellwether — Metaphor taken from the practice of using a castrated sheep (a “wether”) outfitted with a bell, that indicates in which direction the herd is going to be travelling. A bellweather is said to be predictive of the trends to come.

- Bias — A systematic inclination or prejudice in favor of or against something, often leading to unfair or distorted judgments or decisions.

- Big Rocks First — A time-management concept that emphasizes prioritizing the most important tasks (the “big rocks”) before focusing on smaller, less critical tasks. By addressing the key priorities first, you ensure that what matters most gets accomplished, even when other minor tasks (the “pebbles” and “sand”) compete for attention.

- Bikeshedding — a tendency to devote a disproportionate amount of available time to the more trivial and inconsequential matters, while giving short shrift to the most important topics or activities (aka Parkinson’s law of triviality)

- Bin stacking problem — A combinatorial optimization problem where the goal is to efficiently pack a set of objects of varying sizes into a limited number of bins or containers, minimizing the number of bins used or maximizing space utilization. It is often encountered in logistics, manufacturing, and computer science.

- Black and white thinking — Black and white thinking, also known as dichotomous or polarized thinking, is a cognitive distortion where people perceive situations, events, or people in extremes, such as all good or all bad, without recognizing the complexities and nuances in between. This type of thinking can lead to rigid and overly simplistic views, often resulting in emotional distress and conflict in personal and professional relationships.

- Black Swan Theory — A framework by mathematical statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb for understanding rare, unpredictable events that have a massive impact, often missed by conventional risk assessments due to their infrequency and the illusion of predictability.

- Blind spot — A cognitive bias where individuals fail to recognize their own flaws or limitations, often leading to missed risks or opportunities in decision-making.

- Blockchain — A decentralized digital ledger technology that records transactions across many computers securely, preventing retroactive tampering or fraud. The backbone of the cryptocurrency industry.

- Body mass index (BMI) — A measure of body fat based on a person’s weight in relation to their height, used as a general indicator of healthy body weight.

- Boiling frog syndrome — A metaphor for the inability to detect gradual changes in an environment or situation, which eventually leads to detrimental outcomes if left unchecked.

- Bounded economics — A concept rooted in bounded rationality, where economic decision-making is constrained by limitations in information, cognitive abilities, and time. Rather than making perfectly rational choices, individuals and organizations operate within these boundaries, often opting for satisfactory solutions rather than optimal ones (see also: satisficing).

- Bounded rationality — A concept that suggests individuals make decisions with limited information and cognitive resources, leading to suboptimal choices despite rational intent.

- Brainwashing — A process of coercive persuasion and undue influence where an individual’s beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors are manipulated through psychological or physical pressure.

- Bricolage — the creation of art or other creative work from a diverse range of materials and/or influences.

- Broken Windows Theory — A criminological theory that suggests visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows, can encourage further crime and anti-social behavior.

- Burden of proof — The obligation to provide sufficient evidence to support a claim, typically resting on the party that brings the argument or accusation.

- Busy work — Tasks that keep someone occupied but do not contribute meaningful value or progress toward important goals, often used to create the illusion of productivity.

- Butterfly effect — A concept from chaos theory that suggests small changes in initial conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes, highlighting the interconnectedness of complex systems.

- Bystander effect — A social psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to offer help in an emergency situation when others are present, often due to diffusion of responsibility.

- Calvinism — Ideology of a Christian sect known for their fastidious work habits.

- Campbell’s Law — The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures, and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it’s intended to monitor. (see also: Goodhart’s Law)

- Casino capitalism — Casino capitalism refers to an economic system where high-risk financial activities, such as speculative investments and trading, dominate over productive investments in goods and services. This term critiques how financial markets operate like casinos, prioritizing short-term gains and speculative profits over long-term economic stability and growth.

- Catalyst — In a broad sense, a catalyst is something or someone that initiates or accelerates significant change or action without being consumed or altered in the process. In chemistry, it refers to a substance that speeds up a reaction without being used up itself. Similarly, in social or organizational contexts, a catalyst can be an event, person, or idea that sparks transformative progress or change.

- Categorical imperative — Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy, stating that one should behave only in ways they would want to be universal (see also: Golden Rule; ideal universal principle)

- Cathexis — allocating one’s mental or emotional energy to a person, idea, or object, perhaps to an unhealthy degree psychologically.

- Causa-sui project — A term from existential psychology, particularly in the work of Ernest Becker, referring to an individual’s attempt to create meaning and purpose in life by becoming their own cause or creator. It reflects the desire for self-determination and immortality through personal achievements, values, or legacy, as a way to confront the fear of death and insignificance.

- Causation — The relationship between cause and effect, where one event (the cause) directly leads to another event (the effect). In this relationship, changes in the cause are responsible for producing changes in the effect, distinguishing it from mere correlation, where two events may happen together without one necessarily causing the other.

- Central Limit Theorem — mathematical proof showing that any large enough sample size of a population will exhibit a Normal Distribution Curve (aka Bell Curve) for any independently-measured traits.

- Central tendency — A statistical concept that refers to the measure used to determine the center of a data set or the typical value. Common measures of central tendency include the mean (average), median (middle value), and mode (most frequent value), each providing a way to summarize data by identifying its central point.

- Ceteris paribus — A Latin phrase meaning “all other things being equal.” It is used in economics and other fields to analyze the effect of one variable on another while assuming that all other relevant factors remain constant. This helps isolate the impact of a single change in a complex system, similar to the scientific method.

- Chaos Theory — A branch of mathematics and science that studies complex systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, where small changes can lead to vastly different outcomes. Often summarized by the “butterfly effect,” it highlights the unpredictability and non-linear behavior in dynamic systems like weather, ecosystems, or markets.

- Chekhov’s Gun — Literary principle stating that the details of a story should have purpose, and extraneous details omitted.

- Chesterton’s Fence — A principle that argues one should not remove or change an existing structure or system (the “fence”) without first understanding why it was put in place. It encourages caution in making changes, emphasizing the importance of understanding the original purpose before dismissing it as unnecessary.

- Clustering illusion — A cognitive bias where people perceive patterns or clusters in random data, believing that random events are actually related or follow a specific pattern, even when they do not. This bias often leads to overinterpreting coincidences or sequences in data as meaningful.

- Cocoon — Shambhala Buddhist conceptualization of a sort of psychic armor we wear that cuts us off from others in the name of self-protection. The discipline advises one to shed that armor.

- Cognitive extension — Cognitive extension refers to the idea that human cognitive processes can extend beyond the brain to include external tools and environments, such as technology and written language, which enhance and support our mental capabilities. This concept suggests that our minds are not confined within our heads but are instead part of a broader system involving interaction with our surroundings.

- Collective action — A coordinated effort by a group of individuals to achieve a common goal or address a shared issue, often requiring cooperation and collaboration. It plays a crucial role in social, political, and economic contexts, especially when individual actions alone are insufficient to effect meaningful change.

- Collective effervescence — sociological concept of Émile Durkheim to describe when a community or society comes together and bonds over the same thought, theme, message, or action.

- Collective hysteria — A psychological phenomenon where a group of people experiences shared irrational fear, panic, or exaggerated emotions, often spreading quickly through social contagion. This can result in mass panic or delusional beliefs, even in the absence of real danger or evidence, and is typically fueled by rumor, stress, or social dynamics. Also called “moral panic” (examples: the Salem Witch Trials; Satanic Panic of the 1980s).

- Collective narcissism — A belief held by members of a group that their group is superior and deserves special treatment, often accompanied by hypersensitivity to criticism or perceived threats. This inflated sense of group identity can lead to hostility toward outsiders and defensive, aggressive behavior to protect the group’s image. (example: white supremacy)

- Command responsibility — Command responsibility is a legal doctrine in military and international law that holds superiors accountable for crimes committed by their subordinates when they knew or should have known about the actions and failed to prevent or punish them. This principle aims to ensure accountability within the hierarchy of command and is crucial in prosecuting war crimes and crimes against humanity.

- Compound interest — The process by which interest is calculated on both the initial principal and the accumulated interest from previous periods. This results in exponential growth over time, as interest continues to be added to the total amount, making it a powerful concept in finance and investment.

- Condorcet Jury Theorem — mathematical proof showing that if each person on the jury gets it right more than 50% of the time, as numbers get larger the jury as a whole approaches 100% justice. Greatly inspired James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and the Framers of the Constitution.

- Confidence game — Also known as a “con,” it is a deceptive scheme in which a person or group gains the trust of a victim to defraud them, typically by manipulating their emotions or exploiting their desire for gain. The success of the con relies on the victim’s misplaced confidence in the perpetrator.

- Confirmation bias — Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs or opinions. This cognitive bias leads individuals to favor information that supports their views while disregarding or undervaluing evidence that contradicts them. (see also: motivated reasoning)

- Conformity — Conformity is the act of aligning one’s beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors with those of a group or social norm, often due to the desire for acceptance or to avoid conflict. It can be driven by both explicit social pressure and internalized expectations of societal standards.

- Conservation of energy — A principle in physics stating that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another. The total energy in a closed system remains constant over time.

- Conservation of mass — A fundamental concept in chemistry that states mass in a closed system remains constant, regardless of the processes acting inside the system, as matter cannot be created nor destroyed.

- Conservation of momentum — A physics principle asserting that the total momentum of a closed system remains constant if no external forces act on it, meaning momentum is conserved during collisions or other interactions.

- Conspiracy theory — A belief or explanation suggesting that events or situations are the result of a covert, often sinister, group acting in secret (usually a global cabal), typically lacking substantial evidence and ignoring alternative explanations.

- Contagion heuristic — A cognitive shortcut where individuals believe that objects or people can transfer their essence or properties through physical or symbolic contact, often resulting in irrational fears or beliefs about contamination.

- Continued influence effect — The phenomenon in which misinformation continues to influence belief and reasoning even after it has been successfully debunked.

- Conway’s Game of Life — Conway’s Game of Life is a cellular automaton invented by mathematician John Conway in 1970. It consists of a grid of cells that can either be alive or dead, and the cells evolve in steps based on a set of simple rules related to their neighbors. These rules simulate the birth, death, or survival of cells and can lead to complex, unpredictable patterns, making it a famous example of how simple rules can produce emergent behavior and complexity.

- Correlation — A statistical measure that indicates the extent to which two variables move together. A positive correlation means they increase or decrease together, while a negative correlation means they move in opposite directions, but correlation does not imply causation.

- Corruption — The abuse of power or position for personal gain, often involving bribery, fraud, or unethical behavior, undermining trust in institutions or systems.

- Counterfactual thinking — The mental process of imagining alternative outcomes to events that have already occurred, often by asking “what if” questions to explore how different actions might have led to different results.

- Countervailing power — A concept in economics and politics where one group or institution balances the power of another, often to prevent monopolies or ensure fair competition and representation.

- Creative destruction — A term popularized by economist Joseph Schumpeter, referring to the process by which new innovations disrupt and replace outdated industries or technologies, fostering economic progress through continuous renewal.

- Crimes against humanity — Crimes against humanity are severe, widespread, and systematic acts committed against civilians, such as murder, enslavement, torture, and persecution, typically during times of war or conflict. These crimes are considered violations of international law and are prosecuted by bodies like the International Criminal Court (ICC).

- Critical mass — The minimum size or number of participants required for a particular action or event to take off and sustain itself, often used in social movements, markets, or nuclear physics.

- Critical Race Theory — An advanced academic framework that examines how laws and institutions perpetuate racial inequalities and explores the intersection of race, power, and society, often challenging dominant perspectives on race and justice.

- Crossing symmetry — in particle physics, the fact that any particle interaction observed can be anticipated to be replicable with that particle’s antiparticle.

- Crowdfunding — A method of raising small amounts of money from a large number of people, typically via the internet, to fund a project, business, or cause.

- Crowd psychology — The study of how individuals behave differently when they are part of a large group, often leading to irrational or emotional actions influenced by group dynamics rather than personal decision-making.

- Crowdsourcing — The practice of obtaining input, ideas, or services from a large, diverse group of people, usually via the internet, to solve problems or complete tasks more efficiently.

- Cryptocurrency — A digital or virtual form of currency that uses cryptography for secure transactions, operates on decentralized networks based on blockchain technology, and is typically not controlled by any central authority, such as a government or bank. Popular examples include Bitcoin and Ethereum.

- Cult of personality — A situation where a public figure, often a political leader, uses media, propaganda, or other methods to create an idealized, heroic, and worshipful image, fostering uncritical admiration and loyalty from the public.

- Current moment bias — A cognitive bias where people give disproportionate weight to immediate rewards or benefits, often at the expense of long-term gains or future consequences.

- Cybernetics — Cybernetics is an interdisciplinary field that studies systems, control, and communication in animals, machines, and organizations, focusing on how feedback loops and information flow regulate behavior and maintain stability in complex systems.

- Dark matter — Dark matter is an invisible form of matter that doesn’t interact with light or other electromagnetic radiation, but exerts gravitational effects on visible matter. Discovered by astronomer Vera Rubin, dark matter is thought to make up about 85% of the matter in the universe and is crucial for explaining galactic rotation curves and the large-scale structure of the cosmos.

- Dark Triad — A group of three personality traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—characterized by manipulative, self-centered, and exploitative behavior. Individuals exhibiting the Dark Triad traits often seek personal gain with little regard for others, showing tendencies toward deceit, grandiosity, and a lack of empathy.

- DARVO — DARVO stands for Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender, a tactic commonly used by abusers when confronted with their behavior. First, they deny the wrongdoing, then attack the person who brought up the issue, and finally reverse the roles to portray themselves as the victim while casting the accuser as the offender. It’s often used in contexts of manipulation and gaslighting.

- Dead hand of the past — The idea that outdated rules, laws, or decisions continue to exert control over present situations, limiting progress or adaptation to new circumstances.

- Decision tree — A visual or analytical model used to map out decisions and their potential outcomes, helping to systematically analyze different paths and consequences in decision-making.

- Democratic socialism — A political ideology that combines democratic principles, such as free elections and civil liberties, with socialist economic policies that emphasize social ownership and equitable distribution of wealth and resources.

- Denial / denialism — The refusal to accept reality or established facts, often in the face of overwhelming evidence, typically due to psychological defense mechanisms or ideological reasons. Denialism specifically refers to the systematic rejection of consensus on controversial issues (e.g., climate change, evolution).

- Deontology — Deontology is a moral philosophy that emphasizes duty, rules, and obligations as the foundation of ethical behavior. It asserts that actions are morally right or wrong based on adherence to these principles, regardless of the outcomes.

- Derivatives — Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from underlying assets, such as stocks, bonds, or commodities. They are often used for hedging risk or speculative purposes in markets.

- Despotism — Despotism refers to a form of government where a single authority wields absolute power, often ruling through oppression and without regard for the will of the people. This concentration of unchecked authority frequently leads to abuses of power and a lack of individual freedoms.

- Determinism — Determinism is the philosophical idea that all events, including human actions, are determined by prior causes in a cause-and-effect chain. According to this view, free will is an illusion, as everything is a consequence of preceding events and conditions.

- Devil you know — The phrase “devil you know” refers to the idea that a familiar problem or undesirable situation may be preferable to an unknown one. It suggests that people often choose to stick with a known difficulty rather than risk encountering something worse.

- Dichotomy of control — Stoic idea that we should divide the world into things under our control (intentions, efforts) vs. things not in our control (external rewards), and hew to the former vs. the latter for our self-esteem and happiness.

- Diminishing Marginal Utility (DMU) — Diminishing Marginal Utility is an economic principle stating that as a person consumes additional units of a good or service, the satisfaction (utility) gained from each additional unit decreases. In other words, the first unit of consumption provides more utility than the second, and the second more than the third, and so on.

- Discounting positives — Discounting positives is a cognitive bias where individuals downplay or dismiss positive events or attributes, often focusing on negative aspects instead. This can distort perceptions and lead to a pessimistic outlook, even when evidence of success or value is present.

- Disjunction fallacy — The disjunction fallacy occurs when people wrongly assume that the probability of a disjunction (two or more events happening) is less than the probability of one of the individual events, despite logical rules suggesting otherwise. This mistake in reasoning can skew judgments and decision-making.

- Distributions — In statistics, distributions refer to the way values or data points are spread out or arranged within a dataset. Common types of distributions include normal, skewed, and uniform, each describing different patterns of data behavior.

- Diversity — Diversity refers to the inclusion and representation of different perspectives, backgrounds, identities, or viewpoints within a group or system. It is often considered beneficial for fostering innovation, creativity, and broader understanding.

- Domain dependence — Domain dependence refers to the tendency for people’s reasoning or behavior to change depending on the context or “domain” of a problem, even if the underlying logic is the same. This can lead to inconsistencies in decision-making across different areas of life.

- Doublethink — Doublethink, a concept from George Orwell’s 1984, is the act of holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously and accepting both as true. It reflects the capacity for cognitive dissonance in environments of intense ideological control or propaganda.

- Drake Equation — The Drake Equation is a probabilistic formula used to estimate the number of active, communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy. It considers factors such as the rate of star formation, the fraction of those stars with planetary systems, the number of planets that could support life, and the likelihood of life evolving into intelligent beings capable of communication.

- Dr. Fox Effect — The Dr. Fox effect refers to a phenomenon where an engaging and expressive presenter can make a lecture appear informative and satisfying, even if the content is nonsensical or lacking in substance. This effect highlights the power of delivery and presentation skills in shaping perceptions of credibility and knowledge.

- Dunbar Number — The Dunbar Number refers to the cognitive limit to the number of stable social relationships an individual can maintain, typically estimated at around 150 people.

- Dunning-Kruger Effect — The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias where individuals with low ability or knowledge in a particular area overestimate their competence, while highly skilled individuals may underestimate their relative expertise.

- Duverger’s Law — Duverger’s Law is a political theory that in first-past-the-post electoral systems, like the U.S., a two-party system is likely to emerge, as smaller parties struggle to gain representation.

- Easterlin Paradox — named for economist Richard Easterlin, who observed that rising material prosperity in countries doesn’t necessarily lead to greater levels of reported well-being.

- Echo chamber — An echo chamber is a situation in which people are exposed only to information, opinions, or beliefs that reinforce their own views, often amplifying confirmation bias and limiting exposure to differing perspectives.

- Edge of chaos — at the border between order and disorder; a frontier of transition space. A concept from complexity theory describing a transitional space between order and disorder, where systems exhibit the most adaptability and potential for innovation.

- Efficiency — Efficiency refers to the optimal use of resources to achieve the desired outcome with minimal waste, energy, or time.

- Electromagnetic spectrum — The Electromagnetic Spectrum is the range of all types of electromagnetic radiation, from low-frequency radio waves to high-frequency gamma rays, including visible light, microwaves, and X-rays.

- Electron cloud — An electron cloud refers to the probabilistic distribution of where an electron is likely to be found around an atom’s nucleus, based on quantum mechanics, rather than a fixed orbit.

- Elephant and rider — The Elephant and Rider metaphor describes the relationship between the emotional (elephant) and rational (rider) parts of the human mind, suggesting that emotional impulses often dominate but can be guided by rational thought.

- Ellsberg paradox — The Ellsberg Paradox highlights people’s preference for known risks over unknown risks, even when the known risk may have a lower expected value, challenging the predictions of traditional economic decision theory.

- Elsewhere Disease — being convinced that the Real Story is not Here: Here is too boring by far. It’s small and provincial and known already (or so we believe). Excitement is for somewhere far away and exotic.

- Emotional abuse — Emotional abuse is a form of psychological manipulation where one person uses words, actions, or behavior to control, demean, or intimidate another, leading to emotional harm and a loss of self-worth in the victim.

- Emotional intelligence — Emotional intelligence is the ability to recognize, understand, manage, and influence one’s own emotions as well as the emotions of others, fostering better interpersonal relationships and decision-making.

- Emotional labor — Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild introduced the concept of emotional labor in her seminal book “The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling” (1983). Emotional labor refers to the process by which workers manage their emotions to fulfill the emotional requirements of their job. This concept has had a profound impact on understanding the roles and challenges faced by workers in service-oriented industries.

- Emotional reasoning — Emotional reasoning is a cognitive distortion where individuals assume that their emotional reactions reflect objective reality, often leading them to believe that feelings of fear, guilt, or inadequacy are factual, rather than subjective experiences.

- Emperor’s new clothes — The phrase “Emperor’s new clothes” comes from a Hans Christian Andersen story and refers to a situation where people are afraid to speak the truth about something, often for fear of seeming foolish, even when it is plainly obvious that something is wrong or false.

- End Times — End Times refer to eschatological beliefs about the final events of the world or human history, often associated with apocalyptic or religious prophecies regarding the destruction of the world and the ultimate judgment.

- Entropy — Entropy, in thermodynamics, is a measure of disorder or randomness in a system, where systems tend to move from order to disorder over time. In information theory, it represents the unpredictability or uncertainty of information content.

- Epistemic warfare — Epistemic warfare involves the deliberate manipulation or disruption of knowledge, truth, and belief systems, often through disinformation or propaganda, to control public perception and weaken opponents’ ability to make informed decisions.

- E pluribus unum — one out of many, a Latin phrase used on the United States dollar to represent the founding ideals of Thomas Jefferson masterfully explained in the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal.

- Equality under law — Equality under law is the principle that all individuals, regardless of their status, race, gender, or other characteristics, are subject to the same legal codes and entitled to equal protection and treatment by the legal system. It ensures that no one is above the law and that justice is applied uniformly.

- Equilibrium — Equilibrium refers to a state of balance in a system where opposing forces or influences are equal, resulting in no net change. In economics, it describes a condition where market supply and demand are balanced; in physics, it denotes a situation where all acting forces cancel each other out.

- Equity — Equity involves fairness and justice in the way people are treated, striving to provide equal opportunities and address imbalances. In finance, equity represents ownership interest in a company or asset after liabilities are accounted for, such as shareholder equity.

- Eschaton — The eschaton refers to the end of the world or the final event in the divine plan, often associated with ultimate judgment or the arrival of a new era in religious eschatology. In theology, it marks the culmination of history, where cosmic or spiritual events bring about the fulfillment of prophecy.

- Estate tax — An estate tax is a levy imposed on the net value of a deceased person’s assets before distribution to their heirs. It is typically applied by governments on wealth transfers that exceed a certain exemption threshold at the time of death.

- Eternal Rome — “Eternal Rome” refers to the enduring legacy and historical significance of Rome as a city and former empire, symbolizing its lasting impact on culture, law, architecture, and governance throughout Western civilization. The term highlights Rome’s influence that persists across centuries.

- Ethics — Ethics is the branch of philosophy that deals with moral principles, guiding what is right and wrong behavior. The term originates from the Greek word “ethikos,” meaning character, and is closely related to the Latin “moralis,” meaning customs or habits.

- Eucatastrophe — Eucatastrophe is a term coined by author J.R.R. Tolkien to describe a sudden and favorable turn of events in a story, leading from impending disaster to a happy ending. It represents a dramatic reversal where a catastrophe unexpectedly resolves positively.

- Event horizon — An event horizon is the boundary surrounding a black hole beyond which nothing can escape, not even light, due to the immense gravitational pull. It marks the point of no return in spacetime, separating observable events from those that cannot affect an outside observer.

- Exception handling — Exception handling refers to the process of responding to and managing unexpected or anomalous events that disrupt normal operations in computing or organizational processes. It involves identifying, addressing, and resolving edge cases or novel issues to maintain functionality.

- Expected value — Expected value is a statistical concept that calculates the average outcome of a random variable over numerous trials, weighted by their probabilities. It provides a measure of the central tendency, helping to predict long-term results in probabilistic situations.

- Extrapolation — Extrapolation is the method of estimating unknown values by extending or projecting from known data points beyond the established range. It assumes that existing patterns or trends will continue, allowing predictions in new or future contexts.

- Extremism — Extremism refers to holding radical views or beliefs that are far outside the accepted norms of society, often advocating drastic political, religious, or social changes. Such views can lead to actions that challenge or undermine established systems and may pose risks to societal stability.

- Fact-Value Problem — Arose from philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) and the is-ought problem in moral philosophy. It refers to the challenge of distinguishing between descriptive statements (what is) and prescriptive or normative statements (what ought to be) in philosophical discourse. It highlights the difficulty in deriving ethical or moral conclusions directly from factual premises. (see also: naturalistic fallacy, moralistic fallacy)

- False cause — False cause is a logical fallacy where someone mistakenly assumes that because one event follows another, the first event caused the second, without properly establishing a causal link between them. This is also known as post hoc ergo propter hoc.

- False consensus effect — The false consensus effect is a cognitive bias where individuals overestimate the extent to which their beliefs, values, or behaviors are shared by others, assuming that most people think or act the same way they do.

- False flag — A false flag is a deceptive act where a person, group, or state carries out an attack or operation and falsely attributes it to another party, often to justify retaliation or manipulation of public opinion.

- Fate — Fate refers to the belief that events are predetermined and inevitable, often attributed to supernatural or cosmic forces beyond human control. It suggests that a person’s life or outcomes are fixed, and cannot be altered by individual actions or choices.

- Fear of Death — The fear of death, also known as thanatophobia, refers to the anxiety or dread that individuals experience when contemplating their mortality or the end of their existence, often influencing behavior and philosophical outlooks.

- Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance — Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance posits that when individuals experience conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors, they feel psychological discomfort, which motivates them to reduce the inconsistency, often by changing one of the elements involved.

- Fiat currency — Fiat currency is money that has no intrinsic value and is not backed by a physical commodity like gold or silver; its value is derived from the government declaring it as legal tender, which relies on trust in the issuing authority.

- Fiduciary duty — Fiduciary duty is the legal or ethical responsibility of one party, often a trustee or financial advisor, to act in the best interests of another party, prioritizing their client’s welfare above their own personal gains.

- Fifth column — A fifth column refers to a group of secret sympathizers or collaborators within a country or organization who work to undermine it from within, typically in favor of an external enemy or opposing force.

- Filibuster — A filibuster is a political strategy used in legislative bodies, particularly in the U.S. Senate, where a senator prolongs debate or prevents a vote on a bill by speaking for an extended time (now replaced by the “silent filibuster”), often to delay or block its passage.

- First fit algorithm — The first fit algorithm is a simple method for solving the bin packing problem by placing each item into the first available bin that has enough remaining space, without rearranging or looking for the most optimal placement.

- First past the post — First past the post is an electoral system where the candidate with the most votes wins, regardless of whether they have a majority of the votes. It is often used in single-member district systems and tends to favor two-party competition.

- Focusing illusion — The focusing illusion is a cognitive bias where people place disproportionate importance on one aspect of a situation, causing them to misjudge its overall impact on their happiness or well-being. It often leads to overestimating how much a specific factor will affect future outcomes.

- Force multiplier — Force multipliers are tools to help amplify the amount of work you’re able to do. A force multiplier is a strategy or resource that increases the effectiveness and productivity of an individual or group, allowing them to accomplish more with the same amount of effort or resources.

- Fortune-telling — Fortune-telling is a cognitive distortion where a person predicts negative outcomes for events or situations without any concrete evidence, assuming the worst will happen as if it were a certainty.

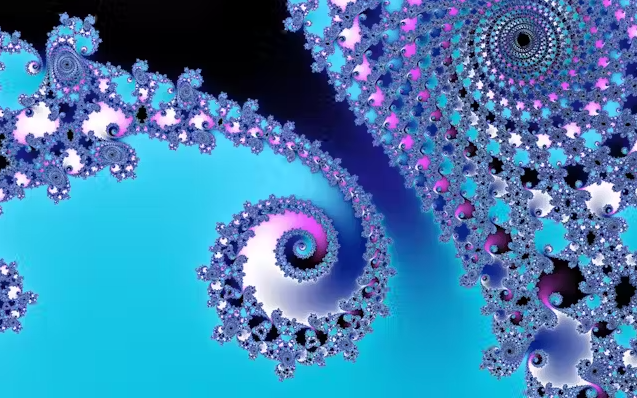

- Fractals — Fractals are complex geometric shapes that can be split into parts, each of which is a reduced-scale copy of the whole, exhibiting self-similarity across different scales. They are found in nature, such as in snowflakes, coastlines, and plants.

- Free markets — Free markets are economic systems where prices, production, and distribution of goods and services are determined by supply and demand with minimal government intervention, allowing businesses and consumers to operate freely.

- Framing effects — Framing effects refer to the way information is presented or “framed,” which can influence decision-making and judgment. The same information can lead to different reactions depending on how it is worded or structured.

- Fredkin’s paradox — Fredkin’s paradox suggests that in decision-making, the closer two choices are in their value or impact, the more time people tend to spend trying to decide between them, even though the decision ultimately has little consequence.

- Free will — Free will is the philosophical concept that individuals have the ability to make choices and decisions independently of external forces or predetermined fate, allowing them to act according to their own volition.

- Friendship paradox — The friendship paradox is the observation that, on average, most people have fewer friends than their friends do. This occurs because individuals with more friends are more likely to be part of other people’s social networks.

- FUBAR’d — FUBAR (short for “F*cked Up Beyond All Recognition/Repair”) is a slang term often used to describe a situation, object, or system that has been so thoroughly ruined or corrupted that it is nearly impossible to fix. It is typically used in informal or military contexts to emphasize extreme dysfunction or chaos.

- FUD — FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt) refers to a strategy used to manipulate public perception by spreading fear, uncertainty, and doubt about a competitor, product, or situation to influence decisions or create distrust.

- Fundamental Attribution Error — The fundamental attribution error is the tendency to overemphasize personal characteristics and underemphasize situational factors when interpreting others’ behavior, assuming that actions reflect innate traits rather than external circumstances.

- Gambler’s fallacy — The gambler’s fallacy is the mistaken belief that if an event occurs more frequently than expected during a given period, it is less likely to happen in the future, or vice versa, despite each event being independent (e.g., flipping a coin).

- Game theory — Game theory is a mathematical framework for analyzing strategic interactions between individuals or groups, where the outcomes depend on the decisions of all participants. It is used in economics, political science, and other fields to study competition and cooperation.

- Gaslighting — Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation in which a person or group makes someone question their own perception, memory, or sanity, often to control or deceive them.

- GDP — GDP, or Gross Domestic Product, is the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific period, typically used as a measure of economic performance and growth.

- General relativity — General relativity is Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, describing how massive objects warp the fabric of spacetime, causing other objects to move along curved paths. It revolutionized our understanding of gravity, predicting phenomena like black holes, gravitational waves, and the bending of light near massive objects.

- Geronticide — Geronticide is the intentional act of killing elderly people, often motivated by societal or economic pressures to reduce the perceived burden of an aging population. This term can also refer to the neglect or harmful policies that lead to premature deaths among the elderly.

- Go-go banking — Go-go banking refers to aggressive, high-risk banking practices characterized by rapid expansion, speculative lending, and the pursuit of maximum short-term profits, often at the expense of long-term stability. The term gained prominence during the 1980s savings and loan crisis, when deregulation enabled financial institutions to engage in risky investments and loans. Go-go banking typically involves loosening credit standards, leveraging heavily, and chasing yields in speculative markets, frequently ending in financial instability or collapse.

- Golden Mean — In philosophy, the Golden Mean is the desirable middle ground between two extremes, as famously advocated by Aristotle. It emphasizes balance and moderation in all aspects of life to achieve virtue.

- Golden Rule — The Golden Rule is the ethical principle of treating others as you would like to be treated. It is a universal concept found in many cultures and religions, advocating empathy and reciprocity.

- Goldilocks Zone — The Goldilocks Zone refers to the habitable zone around a star where conditions are “just right” for life, not too hot or too cold. It’s the range in which liquid water can exist on a planet’s surface, critical for sustaining life as we know it.

- Gold standard — The gold standard is a monetary system in which a country’s currency or paper money has a value directly linked to gold. Countries adhering to this standard maintain a fixed exchange rate between their currency and a specific amount of gold.

- Goodheart’s Law — Goodhart’s Law states that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. This reflects how metrics used to manage a system are often manipulated, leading to unintended outcomes. i.e. anything that can be measured and rewarded will be gamed. (see also: Campbell’s Law)

- Gravitational waves — Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime caused by massive objects accelerating, such as colliding black holes. First predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, they were directly detected in 2015, offering a new way to observe the universe.

- Gravity — Gravity is the force of attraction that pulls objects with mass toward each other. It governs the motion of celestial bodies and is responsible for keeping planets, moons, and satellites in orbit.

- Great Man Theory — The Great Man Theory posits that history is shaped by the impact of influential individuals, typically men of extraordinary intelligence, charisma, or leadership. This idea has been largely critiqued in favor of more complex views of historical causality.

- Great Replacement Theory — The Great Replacement Theory is a racist and far-right conspiracy theory that suggests a deliberate attempt to replace the white population with immigrants or minorities. It has been used to fuel xenophobia and nationalist sentiments.

- Greenwashing — Greenwashing is the deceptive practice where a company or organization exaggerates or falsely advertises its environmental efforts or sustainability to appear more eco-friendly than it truly is. It aims to mislead consumers into believing that products or practices are environmentally responsible, while the actual impact may be minimal or harmful.

- Groundhog Day — Groundhog Day refers to the feeling of experiencing the same situation repeatedly, often with frustration. It’s named after the 1993 Bill Murray film, where the protagonist relives the same day over and over again.

- Groupthink — Groupthink occurs when a group prioritizes consensus and harmony over critical thinking, leading to poor decision-making. It can suppress dissenting opinions and encourage flawed or risky choices by stifling debate.

- Habeas corpus — Habeas corpus is a legal principle that protects individuals from unlawful detention, requiring authorities to present sufficient cause for holding a person in custody. It ensures the right to a fair trial and protects against arbitrary imprisonment.

- Habitus — Habitus, a concept developed by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, refers to the ingrained habits, skills, and dispositions that individuals acquire through life experience. It reflects the influence of social structures on individual behaviors and perceptions.

- Halo effect — The halo effect is a cognitive bias where an overall positive impression of a person or thing influences one’s judgment of their other traits or abilities. For example, someone seen as attractive may also be perceived as more intelligent or capable.

- Hanlon’s Razor — Hanlon’s Razor is an adage that advises not to attribute to malice what can be explained by incompetence or ignorance. It encourages assuming simpler explanations, like error or misunderstanding, over intentional harm.

- Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle — The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics, states that it is impossible to simultaneously know both the exact position and exact momentum of a particle. The more precisely one property is known, the less precisely the other can be determined.

- Herd behavior — Herd behavior refers to the tendency of individuals to mimic the actions or decisions of a larger group, often without independent thought. This phenomenon is common in markets, crowds, and social movements, sometimes leading to irrational or harmful outcomes.

- Heuristics — Heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that simplify decision-making. While they help people make quick judgments, they can also lead to biases and errors in reasoning.

- Hierarchy vs. Fairness — This concept refers to the tension between hierarchical structures, which organize society or institutions based on rank and power, and fairness, which demands equal treatment and justice. These forces often clash in discussions about leadership, meritocracy, and social equity.

- Higgs boson — The Higgs boson is a subatomic particle associated with the Higgs field, which gives other particles their mass. Its discovery in 2012 at CERN confirmed a critical part of the Standard Model of particle physics.

- Hitting rock bottom — “Hitting rock bottom” describes reaching the lowest point in someone’s life, often a crisis that precedes recovery. It represents a turning point where an individual realizes the need for change.

- Hofstadter’s Law — Hofstadter’s Law states that tasks always take longer than expected, even when accounting for Hofstadter’s Law itself. It highlights the difficulty of accurately estimating time in complex projects or tasks.

- Horseshoe Theory — Horseshoe Theory suggests that the political far-left and far-right, while appearing diametrically opposed, often exhibit similar behaviors and ideologies. It implies that extremism at both ends of the spectrum can resemble each other more than centrism.

- Hostile Media Theory — Hostile Media Theory, proposed by Ross & Lepper, suggests that individuals with strong opinions on a topic perceive media coverage as biased against their position, regardless of the actual neutrality of the content. This bias is amplified in polarized environments.

- How many angels can dance on the head of a pin? — This phrase refers to a medieval theological debate about how many angels could fit on a pin’s head, used today to mock overly speculative or trivial discussions. It implies focusing on irrelevant details instead of practical concerns.

- Hydra — In mythology, the Hydra is a serpent-like monster with many heads, and when one head is cut off, two more grow in its place. It symbolizes problems that become worse when addressed incorrectly or superficially, as well as persistent challenges.

- Iatrogenics — Iatrogenics refers to harm caused by medical intervention or treatment, where the cure may be worse than the disease. It highlights the risks of overintervention and the unintended consequences of well-meaning actions in complex systems. (Nassim Taleb is a good source on this)

- Id, ego, superego — Sigmund Freud’s structural model of the psyche consists of the id (the primal, instinctual part of the mind driven by desires), the ego (the rational, decision-making part that mediates between the id and reality), and the superego (the moral conscience shaped by societal norms). Together, they explain human behavior and inner conflict.

- Identifiable Victim Effect — The identifiable victim effect is a psychological phenomenon where people are more likely to empathize with and help an individual whose story is known and personal, compared to a large, faceless group of people. It shows how emotional connection drives charitable behavior.

- Illusory correlation — Illusory correlation is the tendency to perceive a relationship between two variables when no such relationship exists. This cognitive bias can lead to stereotypes, superstitions, and flawed reasoning.

- Impartial spectator — The impartial spectator is a concept from Adam Smith’s moral philosophy describing an imagined, objective observer within ourselves who judges our actions from a neutral, disinterested perspective. This internal figure allows us to evaluate our own behavior by considering how a fair-minded outsider would view it, serving as a moral compass that balances self-interest with social propriety. Smith believed this psychological mechanism was essential for developing sympathy, self-restraint, and ethical judgment in society.

- Imposter Syndrome — Imposter syndrome is the persistent feeling of self-doubt and inadequacy, despite evidence of success or competence. Those experiencing it often believe their achievements are due to luck rather than ability, fearing they’ll be exposed as frauds.

- Inequality — Inequality refers to the uneven distribution of resources, opportunities, or wealth within a society. It can manifest economically, socially, and politically, often resulting in disparities in power and well-being.

- Inflation — Inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services rises, eroding purchasing power over time. It reflects the declining value of currency, often driven by increased demand, supply shortages, or excessive money printing.

- Ingroup bias — Ingroup bias is the tendency to favor one’s own group over outsiders, leading to preferential treatment, loyalty, and positive evaluations of group members. It can contribute to social divisions and prejudice against outgroups.

- Integrative complexity — Integrative complexity is a psychological construct that measures the extent to which an individual or group recognizes multiple perspectives and can integrate these viewpoints into a coherent and nuanced understanding. It reflects the capacity for flexible thinking and problem-solving, often involving the ability to reconcile conflicting information and consider the broader context.

- Interest rate — An interest rate is the percentage charged by lenders to borrowers for the use of money, or the percentage earned on savings or investments. It is a key tool in monetary policy, influencing borrowing, spending, and economic growth.

- Internet of Things (IoT) — The Internet of Things refers to the network of physical objects embedded with sensors, software, and other technologies that enable them to connect and exchange data over the internet. IoT devices range from smart home gadgets to industrial machines, creating interconnected systems that enhance automation and data collection.

- Interposition — Interposition is a controversial political theory suggesting that a state or local government can intervene or “interpose” between the federal government and its citizens to block or resist unconstitutional federal actions. It has historically been invoked in states’ rights debates.

- Interventionism — Interventionism refers to a government’s active involvement in the affairs of other countries or in domestic markets. In international relations, it often involves military or economic actions; in economics, it refers to regulation or direct government involvement in markets.

- Iron law of oligarchy — The Iron Law of Oligarchy, formulated by sociologist Robert Michels, posits that all forms of organization, regardless of how democratic they are at the start, will inevitably evolve into oligarchies. It argues that bureaucratic structures concentrate power into the hands of a few elites.

- Jevons paradox — Jevons Paradox is the idea that increased efficiency in the use of a resource can lead to a greater overall consumption of that resource. For example, more efficient energy use can paradoxically increase total energy demand rather than decrease it.

- Jubilee — Jubilee is a concept of periodic, systematic debt forgiveness originating from ancient Hebrew tradition, where debts were cancelled and land returned to original owners every 50 years. As an economic model, it proposes resetting debt obligations to prevent perpetual indebtedness and wealth concentration, serving as a corrective mechanism against compounding inequality. Modern advocates cite jubilee principles when proposing student loan forgiveness, sovereign debt relief, or other large-scale debt cancellation programs.

- Just-world hypothesis — The just-world hypothesis is the belief that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get, assuming the world is inherently fair. This bias can lead to victim-blaming, as people rationalize misfortune by attributing it to the victim’s actions or character.

- Kakistocracy — Kakistocracy refers to a government run by the least qualified or most corrupt individuals. The term is a critique of leadership marked by incompetence and self-interest.

- Karpman Drama Triangle — The Karpman Drama Triangle is a social model of human interaction in which individuals take on one of three roles: victim, persecutor, or rescuer. These roles create a cycle of conflict and manipulation that hinders healthy resolution of issues.

- Ketman — Ketman refers to the act of outwardly conforming to an oppressive regime while secretly maintaining personal beliefs. The term originated in Eastern Europe under communist rule, describing how people concealed their dissent to avoid persecution.

- Keynesian economics — Keynesian economics, popularized by John Maynard Keynes, advocates for active government intervention to manage economic cycles, especially during downturns. Examples include FDR‘s New Deal, LBJ’s Great Society, and Bidenenomics, which promoted public spending to stimulate demand and reduce unemployment.

- Kleptocracy — A kleptocracy is a government where officials use their power to steal national resources or wealth for personal gain. Such regimes are characterized by rampant corruption and the embezzlement of state funds by those in power.

- Kompromat — Kompromat is a Russian term for compromising material, often used in political blackmail. It refers to the practice of collecting damaging information on individuals to manipulate or control them for political or financial gain.

- KPIs — Key Performance Indicators: metrics and measurements that provide feedback on how well a business is doing at meeting its objectives.

- Kronos Effect — The Kronos Effect refers to the strategy used by dominant companies or institutions to suppress emerging competitors by absorbing them or eliminating threats early on. It’s named after the mythological Greek god Kronos, who devoured his children to prevent them from overthrowing him.

- Laffer Curve — The Laffer Curve is a theory in economics that suggests there is an optimal tax rate that maximizes government revenue. It posits that excessively high tax rates can discourage economic activity, reducing the total tax collected, while lower rates can incentivize growth and increase revenues (see also: supply-side economics, trickle down economics).

- Large Language Model (LLM) — A large language model (LLM) is a type of artificial intelligence that has been trained on vast amounts of text data to understand, generate, and manipulate natural language. These models, such as GPT, are used for a wide range of tasks like text generation, translation, summarization, and answering questions, leveraging deep learning techniques to predict and construct coherent human-like responses.

- Last-place aversion — Last-place aversion describes the phenomenon where people near the bottom of an income distribution oppose wealth redistribution policies. They fear such policies might improve the conditions of those slightly below them, making them relatively worse off in the social hierarchy.

- Law of large numbers — The law of large numbers is a statistical principle that states as the sample size increases, the average of the results becomes more representative of the expected value. In other words, larger data sets lead to more accurate predictions or outcomes.

- Law of triviality — The law of triviality, also known as Parkinson’s Law of Triviality, asserts that organizations often spend disproportionate time on trivial issues while neglecting more significant and complex matters. It highlights how people tend to focus on simple, familiar topics in decision-making processes.

- Least-barricaded gate — The least-barricaded gate refers to the idea that an adversary will attack the most vulnerable or least protected point in a system. It underscores the importance of fortifying weak points in security or defenses.

- Lecturing birds how to fly — This phrase, coined by Nassim Taleb, criticizes the tendency of experts to provide advice or instruction to practitioners who are already naturally skilled in a given area. It reflects the arrogance of over-explaining to those with innate abilities or experience, and the overestimation of academic knowledge or rational means of acquiring skill in society as a whole.

- Lemmings — Lemmings are often used metaphorically to describe individuals who follow the crowd blindly, without independent thought, sometimes leading to disastrous outcomes. The term originates from a misconception that lemmings engage in mass suicidal behavior.

- Letter of the law (vs. spirit of the law) — The “letter of the law” refers to the literal and strict interpretation of legal text, while the “spirit of the law” refers to the intended purpose or broader principles behind the law. Conflict arises when rigid adherence to the letter undermines the law’s original intent.

- Leverage — In finance, leverage refers to the use of borrowed money or other financial instruments to increase potential returns on investment. In broader terms, it can also mean using resources, influence, or advantages to achieve a desired outcome.

- Lifeboat ethics — Lifeboat ethics is a metaphor for resource distribution and moral decision-making in situations of scarcity, suggesting that only a limited number of people can be saved or supported. It raises ethical questions about who gets to survive or benefit when resources are finite.

- Lights were blinking red — “The lights were blinking red” is a shorthand for a visible warning signal or crisis indicator that demands urgent attention but is being overlooked or unaddressed. The phrase comes from the use of flashing red lights in emergency systems, traffic signals, and vehicle warnings—contexts where a blinking red light universally signals immediate danger or the need to stop and reassess, and it was notably used by intelligence officials to describe pre-9/11 warnings and modern critical threats.

- Loaded question — A loaded question is a question that contains a presupposition that traps the respondent into affirming something they may not agree with. It is a form of fallacy or rhetorical trick often used to manipulate the conversation or put someone on the defensive.

- Local min — A local minimum refers to the lowest point within a specific range of a curve, where things may seem as though they have hit rock bottom before turning upward again, representing a temporary low rather than a permanent one.

- Logical fallacies — Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning or argumentation that undermine the logical validity of a claim, often used to mislead or create faulty conclusions, even when the argument appears persuasive at first glance.

- Lone Wolf mythology — The lone wolf mythology is the romanticized idea that individuals, often portrayed as self-sufficient and independent, achieve greatness or significance without any help or collaboration, ignoring the role of community, networks, and external factors in success.

- Long Tail — The concept of the long tail, coined by Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson in 2004, refers to the concept that in digital markets, niche products or services, while individually selling in smaller quantities, collectively make up a large share of total market sales, especially when distribution and storage costs are low.

- Longtermism — Longtermism is a philosophical perspective that emphasizes the importance of making decisions today with a focus on improving the long-term future, often spanning decades, centuries, or even longer, prioritizing the well-being of future generations.

- Loss aversion — Loss aversion is a cognitive bias where people tend to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains, meaning the pain of losing is psychologically more impactful than the pleasure of winning or gaining something.

- Lost Cause — The Lost Cause is a post-Civil War narrative in the U.S. that glorified the Confederacy, portraying it as a noble, righteous fight for states’ rights and downplaying or justifying its connection to slavery, deeply influencing Southern identity and history.

- Lost Einsteins — Lost Einsteins refers to the concept that many potential innovators and inventors, especially from underrepresented or disadvantaged backgrounds, never reach their full potential due to systemic barriers like inequality, lack of access to education, or opportunity.

- Ludic fallacy — The ludic fallacy occurs when people mistakenly apply simplified, game-like rules to real-life situations, underestimating the complexity and unpredictability of real-world scenarios, leading to inaccurate assumptions or predictions.

- Mafia State — Coined by Hungarian sociologist Balint Magyar, a mafia state is a government system where officials, including those in high-ranking positions, engage in criminal activities and form alliances with organized crime networks to consolidate power and wealth. In such states, corruption and illicit practices are normalized, undermining the rule of law and democratic institutions.

- Magical Thinking — Magical thinking is the belief that one’s thoughts, words, or actions can directly influence the outcome of events in ways that defy natural laws or logic. It often stems from a desire to exert control over uncontrollable circumstances, leading to irrational or superstitious behavior.

- Magic helper — In Erich Fromm‘s concept of the “magic helper,” individuals project their desire for salvation or guidance onto an external figure or force, believing that someone or something will rescue them from their struggles. This mental model reflects a dependency on external solutions rather than personal responsibility.

- Magnification — Magnification is a cognitive distortion where individuals exaggerate the significance of negative events or personal failures, making them appear larger and more catastrophic than they really are. This type of thinking often fuels anxiety, stress, and a skewed perception of reality.

- Malignant narcissism — Malignant narcissism is a severe personality disorder characterized by a combination of narcissistic traits, paranoia, antisocial behavior, and sadism. Individuals with this disorder exhibit an extreme need for admiration, a lack of empathy, and a tendency to exploit or harm others for personal gain.

- Manichaean struggle — The Manichaean struggle refers to a worldview that divides reality into a battle between absolute good and absolute evil, often oversimplifying complex issues. This binary thinking fosters an “us versus them” mentality and can justify extreme actions against perceived enemies.

- Man on horseback — A synonym for a demagogue, from French general Georges Ernest Boulanger. A military leader who presents himself as the savior of the country during a period of crisis and either assumes or threatens to assume dictatorial powers.

- Map is not the territory — “The map is not the territory” is a concept indicating that representations of reality, such as maps, models, or descriptions, are not equivalent to reality itself. It underscores the idea that our interpretations and symbols cannot fully encapsulate the complexities and nuances of the actual world.

- Margin of error — The margin of error represents the range within which the true value of a population parameter is expected to lie, based on a sample survey or poll. It provides a measure of uncertainty and is used to understand how precise the results are.

- Marginal benefit — Marginal benefit refers to the additional gain or utility a person receives from consuming or producing one more unit of a good or service. It helps in decision-making by weighing the extra value gained against the cost of the next unit.

- Marginal utility — Marginal utility in economics is the additional satisfaction or benefit derived from consuming one more unit of a good or service. It typically diminishes with each additional unit consumed, a principle known as diminishing marginal utility.

- Market-based Management — Market-based management is a business philosophy developed by Charles Koch that applies free-market principles to organizational management, promoting decentralized decision-making and continuous innovation. It emphasizes value creation through competition and adaptability within the company.

- Market share — Market share refers to the portion of a market controlled by a particular company or product, expressed as a percentage of total sales in that market. It is an indicator of competitiveness and the company’s relative position in its industry.

- Markov chain — A Markov chain is a mathematical system that transitions between different states according to fixed probabilities, where the next state depends only on the current state and not on the sequence of past states. It is widely used in areas like statistics, economics, and machine learning for modeling probabilistic processes.

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs — Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a psychological theory that categorizes human needs into five levels, from basic physiological needs to self-actualization. Individuals must satisfy lower-level needs before they can address higher-level needs, such as self-esteem and personal fulfillment.

- Mean — A statistical measure of central tendency. The mean is the average of a set of numbers, calculated by summing all the values and dividing by the number of values. It provides a measure of central tendency that reflects the typical value in a data set.