Disinformation is more than just false information—it’s a calculated effort to deceive. Unlike misinformation, which spreads by accident or ignorance, disinformation is crafted with precision to manipulate public opinion and sow confusion. Its architects in the right-wing media ecosystem and elsewhere often exploit existing divides—political, social, or cultural—using these cracks in the foundation of society to achieve their aims. Whether the goal is political dominance, economic advantage, or simply the unraveling of trust, disinformation thrives in the chaos it creates. And in today’s digital landscape, it spreads like wildfire, fanning the flames of discord faster than ever before.

But disinformation isn’t just about fake news or conspiracy theories. It’s a full-blown strategy, weaponized by those who understand how to pull the levers of media, technology, and emotion to get what they want. It doesn’t need to be entirely false to do damage—sometimes a well-placed half-truth or a twisted fact is all it takes. The aim is to make us question what’s real and undermine our ability to discern truth from fiction. And this is where vigilance and education come in, arming us with the tools to resist these tactics. In the following disinformation dictionary, in addition to the disinformation definition I’ll break down some of the key terms and tactics used to muddy the waters of truth.

Disinformation Dictionary of Psychological Warfare

The cat is well and truly out of the bag in terms of understanding how easily wide swaths of people can be misled into believing total falsehoods and even insane conspiracy theories that have no basis whatsoever in reality. In their passion for this self-righteous series of untruths, they can lose families, jobs, loved ones, respect, and may even be radicalized to commit violence on behalf of an authority figure. It starts with the dissemination of disinformation — a practice with a unique Orwellian lexicon all its own, collated in the below disinformation dictionary.

Disinformation is meant to confuse, throw off, distract, polarize, and otherwise create conflict within and between target populations. The spreading of falsehoods is a very old strategy — perhaps as old as humankind itself — but its mass dissemination through the media was pioneered in the 20th century by the Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union, the Nazis in Germany, Mussolini‘s Fascists in Italy, and other authoritarian regimes of the early 1900s through the 1940s.

After World War II and the Allies’ defeat of Hitler, the role of disinformation lived on during the Cold War. The Soviet KGB were infamous for their spycraft and covert infiltration of information flows, while the United States experienced waves of anti-Communist paranoia and hysteria fueled by the spread of conspiracist thinking. Psychologists, social scientists, and others did their best to unpack the horrors revealed by the reign of the Nazi regime with a wellspring of research and critical thought about authoritarian personalities and totalitarianism that continues to this day.

The John Birch Society rides again

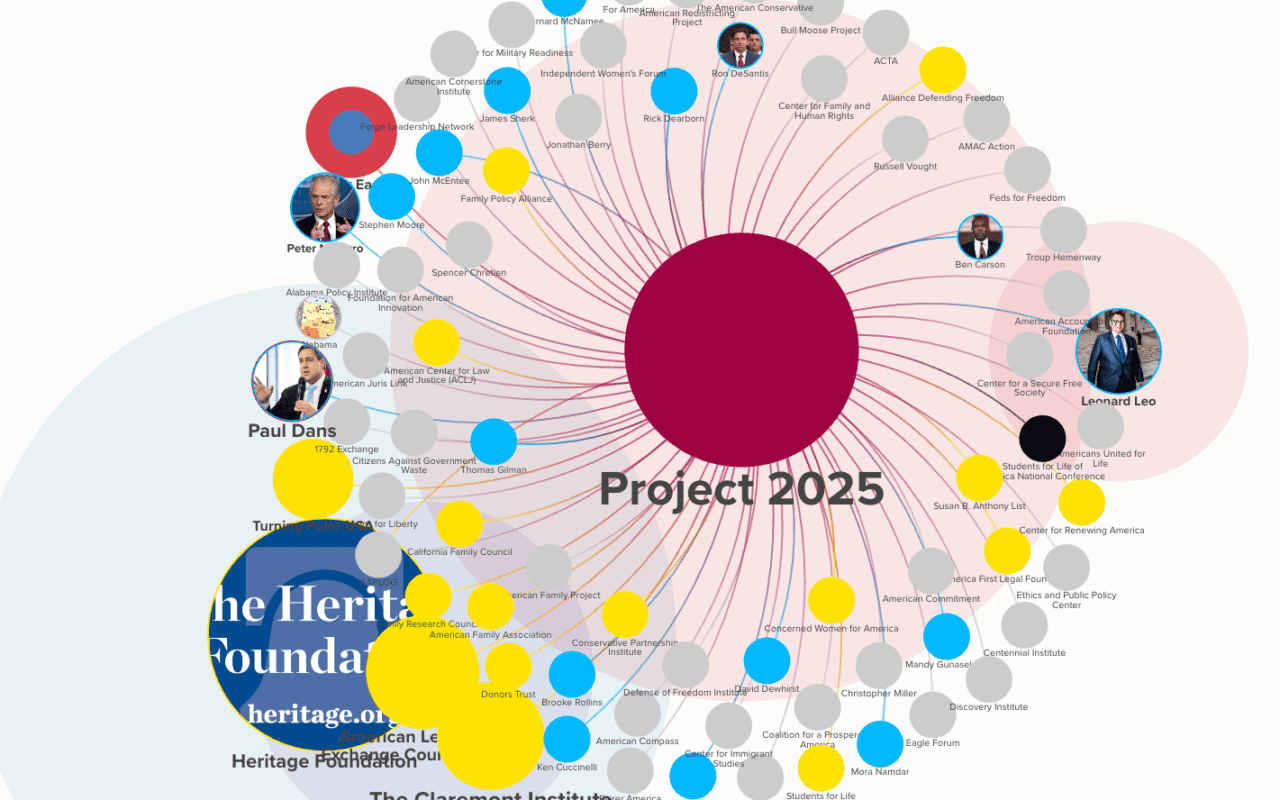

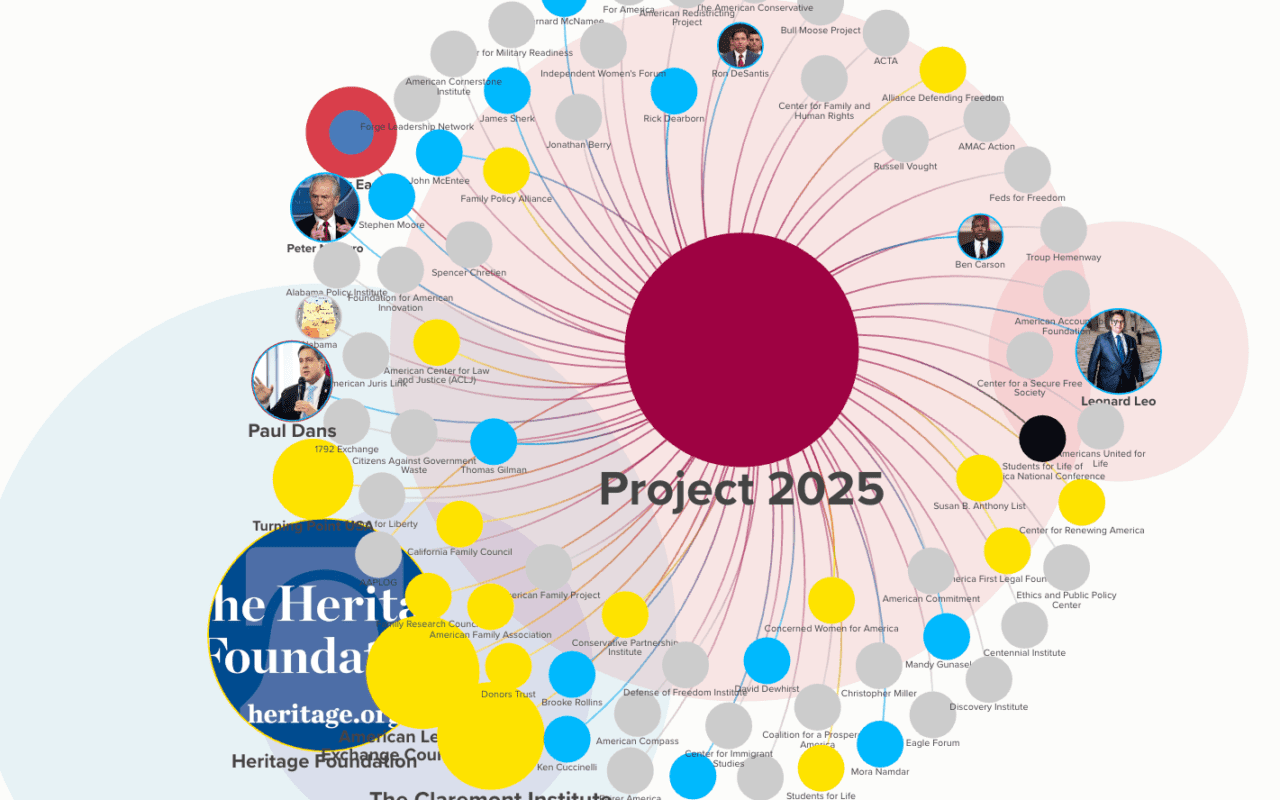

In some ways, we haven’t really moved on yet from the Cold War — in fact, some appear not to have moved on since the New Deal and are hellbent on rolling its provisions back, almost 100 years later. The dregs of the John Birch Society — an organization famously too koo-koo even for William F. Buckley, who excommunicated them from the conservative wing of the Republican Party — live on today in a reconstituted form known as the CNP, or Council for National Policy.

Founded officially in 1981 after almost a decade down in the political trenches radicalizing the right, the CNP is the shadowy organization pulling the strings of many of the set pieces in puppets in today’s political play. In alliance with other powerful networks including the Koch empire, the NRA, and the Evangelical church, the CNP is the group behind the recent hysteria out of nowhere about Critical Race Theory in public schools (where it is not taught).

They are funneling the money of America’s billionaires into absurdist theatrical displays of performance artists who distract America with bread and circuses while the plutocrats make off with the cash in the form of tax cuts, tax breaks, tax carve outs, tax loopholes, tax policy, and other wealth-building sweetheart deals for themselves and their cronies.

The CNP, in partnership with Charles Koch’s massive database of all American voters (and of course, his money), have managed to brainwash the Evangelical flock and various assorted MAGA groups into believing a raft of nonsense from climate change denial to anti-masking to the Big Lie about the 2020 election and much more.

They have leveraged new political technology in order to recruit and radicalize new cult members quickly and at now digital scale — via QAnon, Fox News, the even more extreme aggressively partisan coverage of Newsmax and OANN, and a fleet of “grassroots” astroturf operations peddling their brand of seditious aspirational theocracy to ruralites like it was going out of style… on accounta it is.

US 2024 elections disinformation

As the U.S. now sees the 2024 elections in the rearview mirror, it’s ever more clear the impact of disinformation campaigns on American politics. These orchestrated fakeries are becoming more sophisticated and widespread, targeting voters across social media, messaging apps, and even AI-generated content. These efforts aim to confuse voters, suppress turnout, smear candidates, and undermine trust in the electoral system. In today’s highly polarized environment, disinformation is not just a tool of foreign interference but also a domestic weapon used to influence election outcomes. Understanding these tactics and how they operate is critical for protecting democracy and ensuring a fair election process.

Here is a guide to the main types of election interference disinformation campaigns in progress, so you can be forewarned and forearmed as much as possible:

- Voter Suppression and Confusion

False information is often spread about when, where, or how to vote, confusing voters about eligibility or tricking them with fake polling place closures (see: right-wing operative Jacob Wahl convicted for telecommunications fraud for a voter suppression campaign in MI, NY, PA, IL, and OH in 2020). - Candidate Smear Campaigns

Bad actors fabricate scandals, use manipulated images or videos (“deepfakes”), and spread false claims about candidates to damage their reputations. - Foreign Interference

Nations like Russia, China, and Iran are expected to use fake social media accounts, amplify domestic conspiracy theories, and send targeted messages to influence U.S. elections. - Undermining Election Integrity

Disinformation campaigns spread false claims of widespread voter fraud, misrepresent election security, and attempt to delegitimize results with premature victory declarations or “rigged” election claims.

Platforms and Methods

- Social Media and Messaging Apps

Disinformation spreads rapidly on platforms like Facebook, Twitter (X), TikTok, WhatsApp, and Telegram, where users share and amplify false narratives. - Fake News Websites

Some websites pose as legitimate news sources but are created to deceive readers with false stories that push specific agendas. - AI-Generated Content

The rise of AI allows for the creation of highly realistic but fake images, videos, and texts, making it harder to distinguish truth from falsehood.

Targeted Communities

- Communities of Color

Minority communities are often the focus of disinformation, with tactics designed to exploit shared traumas, concerns, and cultural connections. Misinformation is tailored to specific demographics, often in multiple languages.

Emerging Trends in Disinformation

- AI-Generated Content

AI tools are making it easier to create convincing but fake media, posing new challenges for detecting and countering disinformation. - Prebunking Efforts

Governments and organizations are becoming more proactive, working to debunk false narratives before they spread. - Cross-Platform Coordination

Disinformation is coordinated across different platforms, making it harder to detect and stop, as the false narratives hop from one space to another.

Countermeasures

- Government Agencies

Federal entities are focused on monitoring foreign interference to safeguard elections. - Social Media Content Moderation

Platforms are increasingly using algorithms and human moderators to identify and remove disinformation. - Fact-Checking and Public Education

Non-profits and independent groups work to fact-check false claims and educate voters on how to critically assess the information they encounter. - Media Literacy Initiatives

Public awareness campaigns aim to teach people how to recognize and resist disinformation, helping voters make informed decisions.

Disinformation Definitions Dictionary

This disinformation definition dictionary covers (and uncovers) the terminology and techniques used by disinfo peddlers, hucksters, Zucksters, propagandists, foreign actors, FARA actors, and professional liars of all sorts — including confirmation bias, the bandwagon effect, and other psychological soft points they target, attack, and exploit. From trolling to active measures to “alternative facts,” we dig into the terminology that makes disinformation tick.

This resource will be added to over time as neologisms are coined to keep up with the shifting landscape of fakes, deep fakes, AI disinformation, and alternative timelines in our near and potentially far future.

To learn even more, be sure to check out the Disinformation Books List:

| Term | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| active measures | Russian information warfare aimed at undermining the West | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/active-measures/ |

| alternative facts | Statements that are not supported by empirical evidence. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/alternative-facts/ |

| ambiguity | Ambiguity is utilized in disinformation by presenting information that is deliberately vague or open to multiple interpretations, leading to confusion and uncertainty. This technique exploits the lack of clarity to obscure the truth, allowing false narratives to be introduced and believed without being directly disprovable. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| America First Unity Rally | An event organized by supporters of Donald Trump, held in Cleveland, Ohio, on July 18, 2016, during the RNC that featured speakers known to spread conspiracy theories and unverified claims. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Antifa | Antifa, short for "anti-fascist," is a decentralized movement composed of individuals and groups that oppose fascism and far-right ideologies, often through direct action and protest. The group serves as a frequent scapegoat for the right-wing, who tends to blame Antifa for anything they don't like, without evidence. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/antifa/ |

| anti-government | The neo-Libertarians within the GOP have no more intention of governing than Trump did. Libertarians prefer the government to be non-functional: that's the "smallest" government there is!!They *will* lead us to war, with either Russia, North Korea, Iran, or China most likely. | https://foundations.doctorparadox.net/Ideologies/anti-government |

| anti-vax | The anti-vaccination movement in the U.S. has evolved from 19th-century religious and philosophical objections to modern concerns fueled by misinformation, notably the debunked 1998 study falsely linking the MMR vaccine to autism. The internet and social media have significantly amplified the spread of anti-vaccine disinformation, with various proponents ranging from conspiracy theorists to wellness influencers | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/anti-vax/ |

| assert the opposite of reality | A disinformation technique where false information is presented in a manner that directly contradicts known facts or established reality. This approach is used to confuse, mislead, or manipulate public perception, often by claiming the exact opposite of what is true or what evidence supports. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| astroturfing | Creating an impression of widespread grassroots support for a policy, individual, or product, where little such support exists. | https://foundations.doctorparadox.net/Dictionaries/Politics/astroturfing |

| backfire effect | The backfire effect occurs when individuals are presented with information that contradicts their existing beliefs, leading them to not only reject the new information but also to strengthen their original beliefs. This phenomenon complicates efforts to correct misinformation, as attempts to provide factual corrections can inadvertently reinforce false beliefs | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/backfire-effect/ |

| bandwagon effect | A psychological phenomenon whereby people do something primarily because other people are doing it. | https://doctorparadox.net/data-sets/psychological-biases-list/ |

| the Big Lie | A propaganda technique originally devised by Adolf Hitler, based on the idea that if a lie is colossal and audacious enough, and repeated often, people will come to accept it as truth. This technique relies on the premise that the sheer scale and boldness of the lie makes it more likely to be believed, as people might assume no one could fabricate something so extreme without some basis in reality. | https://doctorparadox.net/gop-myths/gop-big-lies/ |

| black and white thinking | A pattern of thought characterized by polar extremes, sometimes flip-flopping very rapidly from one extreme view to its opposite. Also referred to as dichotomous thinking; polarized thinking; all-or-nothing thinking; or splitting. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/black-and-white-thinking/ |

| blackmail | The demand for payment (or other benefit) in exchange for not revealing negative information about the payee. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/emotional-blackmail/ |

| blaming the victim | A popular strategy with sexual predators, blaming the victim involves alleging that the receipient "had it coming" or otherwise deserved the abuse they suffered at the hands of the blamer (see also: DARVO) | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/what-is-darvo/ |

| book burning | The ritual destruction of books, literature, or other written materials -- usually in a public forum to send a chilling message about ideas that are disallowed by the state. | https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/book-burning |

| bot | A software program performing repetitive, automated tasks -- often used in the dissemination of disinformation. | https://doctorparadox.net/category/technology/bots/ |

| botnets | An interconnected network of bots, often used for nefarious purposes like DDoS attacks or propaganda. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| bullying | Harming, threatening to harm, intimdating, or coercing others into doing your bidding (or for no reason at all) | https://doctorparadox.net/mental-self-defense/how-to-deal-with-bullies/ |

| cathexis | The concentration of one's mental energy on one specific person, idea, or object -- typically to an unhealthy degree. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| chemtrails | The chemtrails conspiracy theory posits that the long-lasting trails left by aircraft, known as contrails, are actually chemical or biological agents deliberately sprayed at high altitudes by government or other agencies for undisclosed purposes. This theory emerged in the late 1990s and has been widely discredited by scientific research, which attributes these trails to normal water-based condensation from aircraft engines | https://doctorparadox.net/conspiracy-theories/chemtrails/ |

| cherry-picking | Cherry-picking refers to the practice of selectively choosing data or facts that support one's argument, while ignoring those that contradict it. This biased approach can misrepresent the overall truth or validity of a situation, leading to skewed conclusions. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/cherry-picking/ |

| @citizentrolling | Former Twitter account of Chuck Johnson, the far-right mega-troll who doxed two New York Times reporters and argued that homosexuality caused the Amtrak derailment. | https://www.wired.com/story/chuck-johnson-twitter-free-speech-lawsuit/ |

| clickbait | Content designed to attract attention and encourage visitors to click on a link. | https://foundations.doctorparadox.net/Dictionaries/Tech/clickbait |

| climate change denialism | Climate change denialism refers to the disbelief or dismissal of the scientific consensus that climate change is occurring and primarily caused by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation. It often involves rejecting, denying, or minimizing the evidence of the global impact of climate change. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/climate-change-denial/ |

| cognitive closure | Propagandists exploit the psychological need for closure by presenting oversimplified explanations or solutions to complex issues, appealing to the desire for quick, definitive answers. This tactic preys on the discomfort with ambiguity and uncertainty, leading individuals to accept and adhere to the provided narratives without critical examination. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/cognitive-closure/ |

| cognitive dissonance | Mental discomfort resulting from holding conflicting beliefs, values, or attitudes -- or from behaving contrary to one's beliefs, values, or attitudes. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/cognitive-dissonance/ |

| cognitive distortion | Irrational, exaggerated, or negative thought patterns that are believed to perpetuate the effects of psychopathological states, such as depression and anxiety. These distortions often manifest as persistent, skewed perceptions or thoughts that inaccurately represent reality, leading to emotional distress and behavioral issues. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| cognitive warfare | Cognitive warfare is a strategy that aims to change the perceptions and behaviors of individuals or groups, typically through the use of information and psychological tactics. This form of warfare targets the human mind, seeking to influence, disrupt, or manipulate the cognitive processes of adversaries, thereby affecting decision-making and actions. (see also: psychological warfare) | https://doctorparadox.net/category/politics/psychological-warfare/ |

| con artist | Someone who swindles others with fake promises. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/con-artist/ |

| confirmation bias | Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one's preexisting beliefs or hypotheses, while giving disproportionately less consideration to alternative possibilities. Disinformation peddlers exploit this bias by crafting messages that align with the existing beliefs of their target audience, thereby reinforcing these beliefs and making their false narratives more convincing and less likely to be critically scrutinized. | https://doctorparadox.net/data-sets/psychological-biases-list/ |

| confirmation loop | A situation where beliefs are reinforced by communication and repetition inside a closed system. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/confirmation-loop/ |

| conspiracy theory | A false narrative or set of narratives designed to create an alternative story or history that distracts from the real truth and/or obscures or absolves the responsibility of those behind the curtain. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/conspiracy-theory-dictionary-from-qanon-to-gnostics/ |

| cultivation theory | A theory which argues that prolonged exposure to media shapes people's perceptions of reality. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/cultivation-theory/ |

| dark money | Dark money refers to political spending by organizations that are not required to disclose their donors or the amounts they spend, allowing wealthy individuals and special interest groups to influence elections without transparency or accountability. This practice gained prominence following the 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which permitted corporations and unions to spend unlimited funds on political campaigns, provided the spending was not coordinated with a candidate's campaign | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/authoritarianism/dark-money/ |

| DARVO | A rhetorical device used in mind control in which the identities of the perpetrator and the victim are reversed, such that the abuser is playing on the sympathies of the abused to help him rewrite the history they both wish to forget. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/what-is-darvo/ |

| deception | Lying; intentionally misleading | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| deep fakes | Fabricated video footage appearing to show an individual speaking | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/deep-fakes/ |

| deep state | The term "deep state" refers to a conspiracy theory suggesting the existence of a hidden or shadowy network of powerful and influential individuals within a government or other organization. These individuals are believed to operate outside the democratic system and pursue their own agenda, often in opposition to the official policies or leaders of the institution. | https://doctorparadox.net/conspiracy-theories/deep-state/ |

| demoshiza | Short for ‘democratic schizophrenics’ -- a Russian slander against citizens of democracies. The ‘demoshiza’ tag also serves a useful purpose in conflating ‘democracy’ with ‘mental illness’. The word ‘democratic’ has an unhappy status in Russia: it is mainly used as an uncomplimentary synonym for ‘cheap’ and ‘low-grade’: McDonald’s has ‘democratic’ prices, the door policy at a particularly scuzzy club can be described as ‘democratic’ – i.e. they let anybody in | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/demoshiza/ |

| denialism | Denialism is the practice of rejecting or refusing to accept established facts or realities, often in the context of scientific, historical, or social issues. It typically involves dismissing or rationalizing evidence that contradicts one's beliefs or ideology, regardless of the overwhelming empirical support. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/science-denialism/ |

| denial of death | The denial of death is a psychological defense mechanism where individuals avoid acknowledging their mortality, often leading to behaviors and beliefs that attempt to give meaning or permanence to human existence. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| denying plain facts | Denying plain facts is the act of refusing to accept established truths, often in the face of overwhelming evidence, typically to maintain a particular narrative or belief system. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| dezinformatsiya | Russian information warfare | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/dezinformatsiya/ |

| digital footprint | The information about a particular person that exists on the Internet as a result of their online activity. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| "dirty tricks" | "Dirty tricks" refer to underhanded, deceptive tactics used in politics, business, or espionage, often involving unethical maneuvers designed to damage opponents or gain an unfair advantage. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| disappearing | In the context of disinformation, disappearing means removing or concealing information, individuals, or objects from public view or records, often to hide evidence or avoid scrutiny. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| diversion | Diversion is a tactic used to shift attention away from a significant issue or problem, often by introducing a different topic or concern, to avoid dealing with the original subject. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| doxxing | Doxxing involves researching and broadcasting private or identifying information about an individual, typically on the internet, usually with malicious intent such as to intimidate, threaten, or harass the person. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| "drinking the Kool-Aid" | Coming to believe the ideology of a cult | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Dunning-Kruger effect | A cognitive bias where individuals with low ability at a task tend to overestimate their ability. | https://doctorparadox.net/models/dunning-kruger-effect/ |

| duty to warn | This refers to a legal or ethical requirement for certain professionals, like therapists or counselors, to break confidentiality and notify potential victims or authorities if a client poses a serious and imminent threat to themselves or others. It's often applicable in scenarios where there's a risk of violence or harm. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| echo chamber | Environment where a person encounters only beliefs or opinions that coincide with their own. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/echo-chamber/ |

| echo chamber effect | A situation in which information, ideas, or beliefs are amplified or reinforced by transmission and repetition inside an enclosed system. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| ego defense | Ego defense mechanisms are psychological strategies employed by the unconscious mind to protect an individual from anxiety or social sanctions and to provide a refuge from a situation with which one cannot currently cope. These mechanisms can lead to the formation of false beliefs, as they may distort, deny, or manipulate reality as a way to defend against feelings of threat or discomfort. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/ego-defense/ |

| election denialism | Election denialism is the act of refusing to accept the legitimate results of an electoral process, often based on unfounded claims of fraud or manipulation. It undermines the democratic process and can lead to political instability or violence. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/election-denial/ |

| emotional abuse | Emotional abuse is a form of abuse characterized by a person subjecting or exposing another to behavior that may result in psychological trauma, including anxiety, chronic depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder. It involves tactics like belittling, constant criticism, manipulation, and isolation to control or intimidate the victim. | https://doctorparadox.net/tag/emotional-abuse/ |

| emotional blackmail | Emotional blackmail is a manipulation tactic where someone uses fear, obligation, and guilt to control or manipulate another person. It often involves threats of punishment, either directly or through insinuation, if the victim does not comply with the manipulator's demands. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/emotional-blackmail/ |

| emotional manipulation | Emotional manipulation involves using underhanded tactics to influence and control someone else's emotions or actions for the manipulator's benefit. It can include gaslighting, guilt-tripping, and playing the victim to gain sympathy or compliance. | https://doctorparadox.net/tactics-of-emotional-predators/ |

| empty promises | Empty promises refer to assurances or commitments made with no intention or ability to fulfill them. They are often used to placate or appease someone in the moment but lead to disappointment and mistrust when the promised action or change doesn’t occur. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| extortion | Extortion is a criminal offense that involves obtaining something of value, often money, through coercion, which includes threats of harm or abuse of authority. It's a form of manipulation where the perpetrator seeks to gain power or material benefits by instilling fear in the victim. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| fact-checking | The act of checking factual assertions in non-fictional text to determine the veracity and correctness of the factual statements. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/fact-checking/ |

| fake audience | Bots or paid individuals used to create an illusion of more support or interest than is really the case. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| fake news | Fake news refers to fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent, often created to mislead or deceive readers, viewers, or listeners. It is intentionally and verifiably false, and is disseminated through various media channels, typically for political or financial gain. Trump is fond of mislabelling actual journalism outlets as "fake news" as a way to discredit them. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| false consciousness | Part of Marxist theory regarding the phenomenon where the subordinate classes embody the ideologies of the ruling class, diverting their self-interest into activities that benefit the wealthy who are taking advantage of them. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| false equivalence | False equivalence is a logical fallacy that occurs when two opposing arguments or issues are presented as being equally valid, despite clear differences in quality, validity, or magnitude. It involves drawing a comparison between two subjects based on flawed or irrelevant similarities, leading to a misleading or erroneous conclusion. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| false flag | covert operations designed to deceive by appearing as though they are carried out by other entities, groups, or nations than those who actually executed them | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/false-flag/ |

| false narrative | A false narrative is a deliberately misleading or biased account of events, designed to shape perceptions or beliefs contrary to reality. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| fifth world war | Non-linear war; the war of all against all -- a term coined by Putin's vizier Vladislav Surkov. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/fifth-world-war/ |

| filter bubble | Intellectual isolation that can occur when websites use algorithms to selectively assume the information a user would want to see. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/filter-bubble/ |

| flying monkeys | In a psychological context, "flying monkeys" refers to individuals who are manipulated to harass or undermine someone on behalf of a manipulative person, often in situations of abuse or narcissism. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/flying-monkeys/ |

| Fox News Effect | This term describes the significant influence that watching Fox News can have on viewers' political views, often swaying them towards more conservative positions. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| framing effect | The way information is presented so as to emphasize certain aspects over others. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| fraud | Fraud is the intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| GamerGate | Early harbinger of the alt-right, emerging on social media and targeting professional women in the video games industry | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| gaslighting | Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation where a person or a group covertly sows seeds of doubt in a targeted individual, making them question their own memory, perception, or judgment. | https://doctorparadox.net/mental-self-defense/gaslighting/ |

| "global cabal" | euphemism in far-right Russian discourse to refer to a perceived "Jewish conspiracy" behind the international order of institutions like NATO and the EU | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/authoritarianism/global-cabal/ |

| globalization | The process of increased interconnectedness and interdependence among countries worldwide, characterized by the free flow of goods, services, capital, and information across borders. | https://foundations.doctorparadox.net/Dictionaries/Economics/globalization |

| greenwashing | A deceptive practice where a company or organization overstates or fabricates the environmental benefits of their products or policies to appear more environmentally responsible. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| grooming | A manipulative process used by predators to build a relationship, trust, and emotional connection with a potential victim, often for abusive or exploitative purposes. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| groupthink | The practice of thinking or making decisions as a group in a way that discourages creativity or individual responsibility -- making poor decision-making more likely. | https://doctorparadox.net/models/bad-models/groupthink/ |

| Guccifer 2.0 | A pseudonymous persona that claimed responsibility for hacking the Democratic National Committee's computer network in 2016, later linked to Russian military intelligence. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| hate speech | Speech that attacks or demeans a group based on attributes such as race, religion, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, disability, or gender, often inciting and legitimizing hostility and discrimination. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| The Heartland Institute | The Heartland Institute is an American conservative and libertarian public policy think tank focused on promoting free-market solutions to various social and economic issues. It is well-known for its skepticism of human-caused climate change and its advocacy against government regulations. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/the-heartland-institute/ |

| hoax | A deliberately fabricated falsehood made to masquerade as truth. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/hoax/ |

| honeypot | In cybersecurity, a strategy that involves setting up a decoy system or network to attract and trap hackers, thereby detecting and analyzing unauthorized access attempts. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/honeypot/ |

| horseshoe theory | Political model in which the extreme left has a tendency to sometimes adopt the strategies of the extreme right. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| hybrid warfare | Hybrid warfare is a military strategy that blends conventional warfare, irregular warfare, and cyberwarfare with other influencing methods, like fake news, diplomacy, and foreign electoral intervention. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/ |

| hypnosis | Hypnosis is a mental state of heightened suggestibility, often induced by a procedure known as a hypnotic induction, which involves focused attention, reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| influence techniques | Influence techniques encompass a range of tactics and strategies used to sway or manipulate someone's beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors, often employed in marketing, politics, and interpersonal relationships to subtly or overtly change people's minds or actions. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/influence-techniques/ |

| information overload | Exposure to or provision of too much information or data. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| information terrorists | Media personalities and professionals working against the interests of democracy in the United States. Many amplify their messages through automation and human networks, creating a Greek Chorus-like cacaphony of fake support for unpopular positions. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| information warfare | Information warfare involves the use and management of information to gain a competitive advantage over an opponent, often involving the manipulation or denial of information to influence public opinion or decision-making processes. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/ |

| InfoWars | InfoWars is a far-right American conspiracy theory and fake news website and media platform led by Alex Jones, known for its promotion of numerous unfounded and false conspiracy theories. | https://foundations.doctorparadox.net/People/Alex+Jones#Early+life+and+Infowars.com |

| Intermittent reinforcement | In the context of manipulation, intermittent reinforcement is a behavior conditioning technique where rewards or punishments are given sporadically to create an addictive or obsessive response, making a person more likely to repeat a behavior. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| jumping to conclusions bias | This is a cognitive bias that involves making a rushed, premature judgment or decision without having all the necessary information, often leading to misinterpretation or misinformation. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| kleptocracy | form of government in which the leaders harbor organized crime rings and often participate in or lead them; the police, military, civil government, and other governmental agencies may routinely participate in illicit activities and enterprises. | https://doctorparadox.net/category/politics/kleptocracy/ |

| kompromat | Kompromat is a Russian term that refers to the gathering of compromising materials on a person or entity to be used for blackmail, manipulation, or public shaming, often for political purposes. It typically involves collecting sensitive, embarrassing, or incriminating information to exert influence or gain leverage over individuals or groups. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/kompromat/ |

| Mafia state | A systematic corruption of government by organized crime syndicates. A term coined by former KGB/FSB agent Alexander Litvinenko. See also: kleptocracy | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/authoritarianism/mafia-state/ |

| malignant envy | Malignant envy refers to a deep-seated, destructive form of envy that desires to spoil or harm the qualities, possessions, or achievements of someone else, often arising from feelings of inferiority or failure. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| malignant narcissism | Malignant narcissism is a psychological syndrome comprising an extreme mix of narcissism, antisocial behavior, aggression, and sadism, often manifesting in manipulative and destructive tendencies. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/authoritarianism/malignant-narcissism/ |

| malware | Malware, short for malicious software, refers to any software intentionally designed to cause damage to a computer, server, client, or computer network. It encompasses a variety of forms, including viruses, worms, spyware, and ransomware, aiming to exploit, harm, or unauthorizedly access information and systems. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/malware/ |

| manipulative media | Media that is altered to deceive or harm. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Marxist | A catch-all derogatory slur for Democrats | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| maskirovka | war of deception and concealment | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/maskirovka/ |

| mass hypnosis | Mass hypnosis refers to a phenomenon where a large group of people, often in a crowd or under the influence of media, enter a state of heightened suggestibility, making them more susceptible to persuasion and collective beliefs, often used in the context of propaganda and political manipulation. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Mean World Syndrome | Mean world syndrome is a term in media theory that describes how people who consume large amounts of violent or negative media content tend to perceive the world as more dangerous and hostile than it really is. This phenomenon, coined by communications professor George Gerbner, suggests that heavy exposure to media violence shapes viewers' beliefs about reality, increasing their fear and anxiety about being victimized. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/mean-world-syndrome/ |

| media bias | The perceived bias of journalists and news producers within the mass media. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| meme warfare | The use of memes to disseminate an ideology or counter its adversaries. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| men's rights | The men's rights movement is a movement that advocates for the rights and interests of men, often focusing on issues like family law, alimony, and false rape accusations, but it has faced criticism for spreading misinformation and fostering anti-feminist sentiments. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| microtargeting | Microtargeting is a marketing strategy that analyzes consumer data to identify and target specific segments of a population with highly personalized messages, often through social media and online platforms. In disinformation campaigns, it's used to manipulate public opinion by spreading tailored misinformation to vulnerable groups, exploiting their beliefs or fears for political or ideological gain. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/microtargeting/ |

| mind control | Mind control refers to the process or act of using psychological techniques to manipulate and control an individual's thoughts, feelings, decisions, and behaviors, often associated with cults, brainwashing, and coercive persuasion. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| minimizing | Minimizing is a manipulation technique where the severity, importance, or impact of an issue, behavior, or event is downplayed, often to deflect responsibility or diminish perception of harm. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| misinformation | Misinformation is false or inaccurate information that is spread, regardless of intent to deceive, which can include rumors, hoaxes, and errors, often leading to misunderstanding or misinterpretation of facts. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| money laundering | Money laundering is the illegal process of making large amounts of money generated by criminal activity, such as drug trafficking or terrorist funding, appear to have come from a legitimate source. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| moral panic | A widespread feeling of fear, often an irrational one, that some evil threatens the well-being of society. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| motivated reasoning | Motivated reasoning is a cognitive bias that causes individuals to process information in a way that suits their pre-existing beliefs or desires, often leading to skewed or irrational decision-making and reinforcing misinformation or false beliefs. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/authoritarianism/motivated-reasoning/ |

| moving the goalposts | Changing the rules after the game is played, when one side doesn't like the outcome. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| "myth of tech misogyny" | A form of denialism made popular by alt-right commentator and troll Milo Yiannopoulos, used to discredit feminist discussions about the tech and gaming industry's notorious levels of misogyny. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| naive realism | Naive realism is the cognitive bias leading individuals to believe that they perceive the world objectively and that people who disagree with them must be uninformed, irrational, or biased. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| narcissistic rage | Narcissistic rage is an intense, often violent, emotional outburst by someone with narcissistic personality disorder, usually triggered by a perceived threat to their self-esteem or self-worth. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/narcissistic-rage/ |

| narcissistic supply | Narcissistic supply refers to the attention, admiration, emotional energy, or other forms of "supply" that a person with narcissistic tendencies seeks from others to bolster their self-esteem and self-image. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| narrative framing | The context or angle from which a news story is told. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| The National Enquirer | The National Enquirer is an American tabloid newspaper known for its sensationalist and often unsubstantiated reporting, typically focused on celebrity gossip, scandals, and conspiracy theories. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| neurolinguistic programming (NLP) | Neurolinguistic Programming is a controversial approach to communication, personal development, and psychotherapy, which claims that there is a connection between neurological processes, language, and behavioral patterns learned through experience. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/neurolinguistic-programming-nlp/ |

| nihilism | Nihilism is a philosophical belief that life lacks objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value, and often rejects established norms and values, sometimes leading to skepticism and pessimism about the world. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| non-linear warfare | Non-linear warfare is a military and geopolitical strategy that involves unconventional, unpredictable tactics that do not follow traditional lines of conflict, often blending military and non-military means, including cyber attacks, disinformation, and economic tactics. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/ |

| novichok | military-grade nerve agent developed by Russia and used in the poisoning of former FSB agent turned Putin critic Andrei Skripal and his daughter in Lonson in March, 2018 | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/novichok/ |

| one-way street | Expect loyalty from you while offering none in return | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| oppo | short form of opposition research | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Overton window | The range of ideas tolerated in public discourse. | https://doctorparadox.net/models/ |

| paranoia | Nurturing and maintaining enemies | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/paranoia/ |

| passive aggressive | Passive aggressive behavior is a way of expressing negative feelings indirectly rather than openly addressing them, often involving subtle actions or inactions intended to annoy, obstruct, or control others. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| photo manipulation | Altering a photograph in a way that distorts reality. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| PizzaGate | PizzaGate was a debunked conspiracy theory that falsely claimed high-ranking Democratic Party officials and U.S. restaurants were involved in an underage human trafficking ring, which was widely disseminated online and led to dangerous real-world consequences. | https://doctorparadox.net/conspiracy-theories/pizzagate/ |

| plausible deniability | Plausible deniability refers to the ability of people, typically senior officials in an organization, to deny knowledge of or responsibility for any damnable actions committed by others in an organizational hierarchy because of a lack of evidence that can confirm their participation. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| playing the victim | Playing the victim is a manipulative technique where a person portrays themselves as a victim of circumstances or others' actions in order to gain sympathy, justify their own behavior, or manipulate others. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| political advertising | Political advertising encompasses the use of media and communication strategies by politicians and parties to influence public opinion and voter behavior, often highlighting policy positions, achievements, or criticisms of opponents. In disinformation campaigns, it can be strategically deployed to spread false or misleading information, aiming to manipulate public perception and undermine trust in political processes or adversaries. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| post-truth | Post-truth describes a cultural and political context in which debate is framed largely by appeals to emotion disconnected from the details of policy, and by the repeated assertion of talking points to which factual rebuttals are ignored. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| prebunking | Prebunking is a proactive strategy aimed at preventing the spread of disinformation by exposing individuals to weakened versions of common misleading techniques before they encounter them. This method helps build resilience by teaching people how to critically analyze and question the validity of information they come across. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/prebunking/ |

| projection | Projection is a psychological defense mechanism where a person unconsciously denies their own negative qualities by ascribing them to others, often leading to blame-shifting and misinformation. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/projection/ |

| Project Lakhta | Internal name for the operation that Prigozhin's IRA was running to interfere in elections across the Western world, according to the Mueller indictments. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/project-lakhta/ |

| propaganda | Propaganda is the systematic dissemination of often biased or misleading information, used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/authoritarianism/propaganda/ |

| psychographic profiles | Psychographic profiling in political microtargeting involves analyzing individuals' personality traits, values, interests, and lifestyles to tailor messages that resonate on a deeply personal level, often used to influence voter behavior. This technique has raised concerns about disinformation, as it allows for the manipulation of perceptions and opinions by targeting susceptible segments of the population with tailored, and potentially misleading, content. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| psychopathy | Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by persistent antisocial behavior, impaired empathy and remorse, and bold, disinhibited, and egotistical traits. | https://doctorparadox.net/psychology/psychopaths/ |

| PUA | PUA, or Pick-Up Artist, refers to a person who practices finding, attracting, and seducing sexual partners, often using deceptive and manipulative tactics. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| QAnon | QAnon is a disproven and discredited far-right conspiracy theory alleging that a secret cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring and plotting against former U.S. President Donald Trump. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/what-is-qanon/ |

| received wisdom | Received wisdom refers to ideas or beliefs that are generally accepted as true without being critically examined, often perpetuating existing biases or misconceptions. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| red herring | Something that misleads or distracts from a relevant or important question. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| #releasethememo | "#ReleaseTheMemo" was a social media campaign promoting the release of a classified memo written by U.S. Representative Devin Nunes that alleged abuses of surveillance by the FBI and the Justice Department in the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| retcon | Retcon, or retroactive continuity, is the alteration of previously established facts in a fictional work, often seen in comics, movies, and TV shows, used to reshape the narrative. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| running out the clock | Running out the clock is a strategy in debates or negotiations where one party intentionally delays or prolongs the process until a deadline is reached, limiting the ability of the other side to respond or take action. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| sadism | Sadism is the tendency to derive pleasure, especially sexual gratification, from inflicting pain, suffering, or humiliation on others. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| samizdat | Self-publishing material that is banned by the state | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/samizdat/ |

| satire | The use of humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people's stupidity or vices. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| selective exposure | Selective exposure is the tendency to favor information which reinforces one's pre-existing views while avoiding contradictory information, a significant factor in the spread of misinformation. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| shame | Shame is a complex emotion that combines feelings of dishonor, unworthiness, and embarrassment, often used in social or psychological manipulation to control or degrade others. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| shit-posting | Shit-posting is the act of publishing deliberately provocative or irrelevant posts or comments online, typically to upset others or divert attention from a topic, often seen in online forums and social media. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/shitposting/ |

| siloviki | Russian term for those who have backgrounds and employment in the Russian power ministries -- security services, the military, and police; and more specifically a reference to Putin's security cabal. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/siloviki/ |

| Snow Revolution | Popular protests beginning in Moscow in 2011, demanding the reinstatement of free elections & the ability to form opposition parties. Hundreds if not thousands of protestors were detained on the first day of action (Dec 5), continuing over the next 2 years as punishments grew increasingly harsh and more activists were sent to penal colonies. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/cold-war-dictionary/snow-revolution/ |

| social bots | Automated accounts that use AI to influence discussions and promote specific ideas or products. | https://doctorparadox.net/category/technology/bots/ |

| social hierarchies | Social hierarchies refer to the structured ranking of individuals or groups within a society, based on factors like class, race, wealth, or power, often influencing people's behavior, opportunities, and interactions. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| social proof | A psychological phenomenon where people assume the actions of others in an attempt to reflect correct behavior for a given situation. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| sockpuppet accounts | Fake social media accounts used by trolls for deceptive and covert actions, avoiding culpability for abuse, aggression, death threats, doxxing, and other criminal acts against targets. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/hybrid-warfare/sockpuppet-accounts/ |

| source amnesia | Source amnesia refers to the phenomenon where one can recall information but not the source it came from, a situation that exacerbates the spread and entrenchment of misinformation. In the digital age, this contributes significantly to the challenges of distinguishing credible information, as misinformation can spread widely once detached from its dubious origins. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/source-amnesia/ |

| source credibility | The perceived trustworthiness or authority of the source of information. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| "sovereign democracy" | system in which democratic procedures are retained, but without any actual democratic freedoms; brainchild of Vladislav Surkov | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Special Mission | In the context of disinformation, a "Special Mission" often refers to covert, deceptive operations or tasks assigned under the guise of legitimacy, typically to influence public opinion or political situations. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| spin | A form of propaganda that involves presenting information in a biased way. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| "spirit cooking" | Spirit cooking refers to a form of performance art popularized by Marina Abramović, which uses ritualistic elements and symbolic gestures in a dinner party setting, often incorporating themes of life, death, and renewal. The term gained widespread attention and controversy in the context of John Podesta's emails released by WikiLeaks in 2016, where an invitation to a spirit cooking dinner led to various conspiracy theories, though it was associated with Abramović's art rather than any literal practice. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| splitting | See the world as with them or against them; an extension of black and white thinking. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| stochastic terrorism | Refers to the use of mass communication to incite random individuals to carry out violent or terrorist acts that are statistically predictable but individually unpredictable. It involves the dissemination of rhetoric and propaganda that demonizes certain groups or individuals, creating an environment where violence is implicitly encouraged without directing specific acts. | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/stochastic-terrorism/ |

| stonewalling | Stonewalling is a refusal to communicate or cooperate, such as by not responding to questions or withdrawing from a conversation, often used as a tactic to avoid confrontation or evade accountability. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Stop the Steal | "Stop the Steal" was a slogan and movement promoted by supporters of former U.S. President Donald Trump, falsely claiming widespread voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election in an attempt to overturn the results. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| Tarasoff rule | The Tarasoff rule refers to a legal principle requiring mental health professionals to breach confidentiality and notify potential victims if a client makes credible threats of violence against them, stemming from a 1976 California court case. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| thought-stopping | Thought-stopping involves the deliberate cessation of unwanted or disturbing thoughts, often used in ideological or religious indoctrination to avoid critical thinking and maintain control over beliefs. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| torture | Torture is the act of inflicting severe physical or psychological pain or suffering on someone, typically to extract information, punish, intimidate, or for the personal gratification of the torturer. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| troll farms | A group of individuals hired to produce a large volume of misleading or contentious social media posts. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| trolling | Trolling is the act of making unsolicited or provocative comments online, often anonymously, with the intent of upsetting others, provoking a reaction, or disrupting discussions. | https://foundations.doctorparadox.net/Dictionaries/Tech/trolling |

| undue influence | Undue influence involves the exertion of excessive pressure or manipulation by one person over another in a relationship, typically to gain control, decision-making power, or exploit the vulnerable party. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| urban legend | A humorous or horrific story or piece of information circulated as though true. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| viral misinformation | False information that spreads rapidly through social media networks. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| wallpaper effect | The "wraparound" pervasiveness of Right-wing Media and its Brainwashing effects at scale | https://doctorparadox.net/dictionaries/disinformation-dictionary/wallpaper-effect/ |

| whisper campaign | A method of persuasion in which damaging rumors or innuendo are spread about the target. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| white male identity politics | White male identity politics is a form of identity politics centered on the interests, experiences, and perspectives of white men, often emphasizing racial and gender hierarchies and reacting against perceived threats to white male dominance. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| white nationalism | White nationalism is a political ideology that advocates for the self-governance and superiority of white people, often emphasizing racial purity and the creation of a white-only state. | https://doctorparadox.net/save-democracy/right-wing-ideologies/white-nationalist-beliefs/ |

| white terrorism | White terrorism refers to acts of terrorism committed by individuals or groups motivated by white supremacist or white nationalist ideologies, typically aimed at advancing racial and ethnic hierarchies. | https://doctorparadox.net/ |

| yellow journalism | Journalism that is based upon sensationalism and crude exaggeration. | https://foundations.doctorparadox.net/Dictionaries/Politics/yellow+journalism |