Black and white thinking is the tendency to see things in extremes, viewing the world through a very polarized lens. Even complex moral issues are seen as clearcut, with simple right and wrong answers and no gray areas in between.

Also referred to as all-or-nothing thinking or dichotomous thinking, black and white thinking is a very rigid and binary way of looking at the world. Black and white thinkers tend to categorize things, events, people, and experiences as either completely good or completely bad, without acknowledging any nuance or shades of gray. This can manifest in various aspects of their lives including relationships, decision-making, and self-evaluation. Black and white thinking can be a defense mechanism, as it provides a sense of certainty and control in situations that are complex, uncertain, or anxiety-provoking.

For example, a person who engages in black and white thinking may view their work performance as either completely successful or a complete failure, without considering any middle ground. They may view themselves as either a “good” or “bad” person, based on a single action or mistake. This type of extreme thinking can lead to feelings of extreme anxiety, depression, and self-doubt, as well as difficulties in personal and professional relationships.

Black and white thinking in political psychology

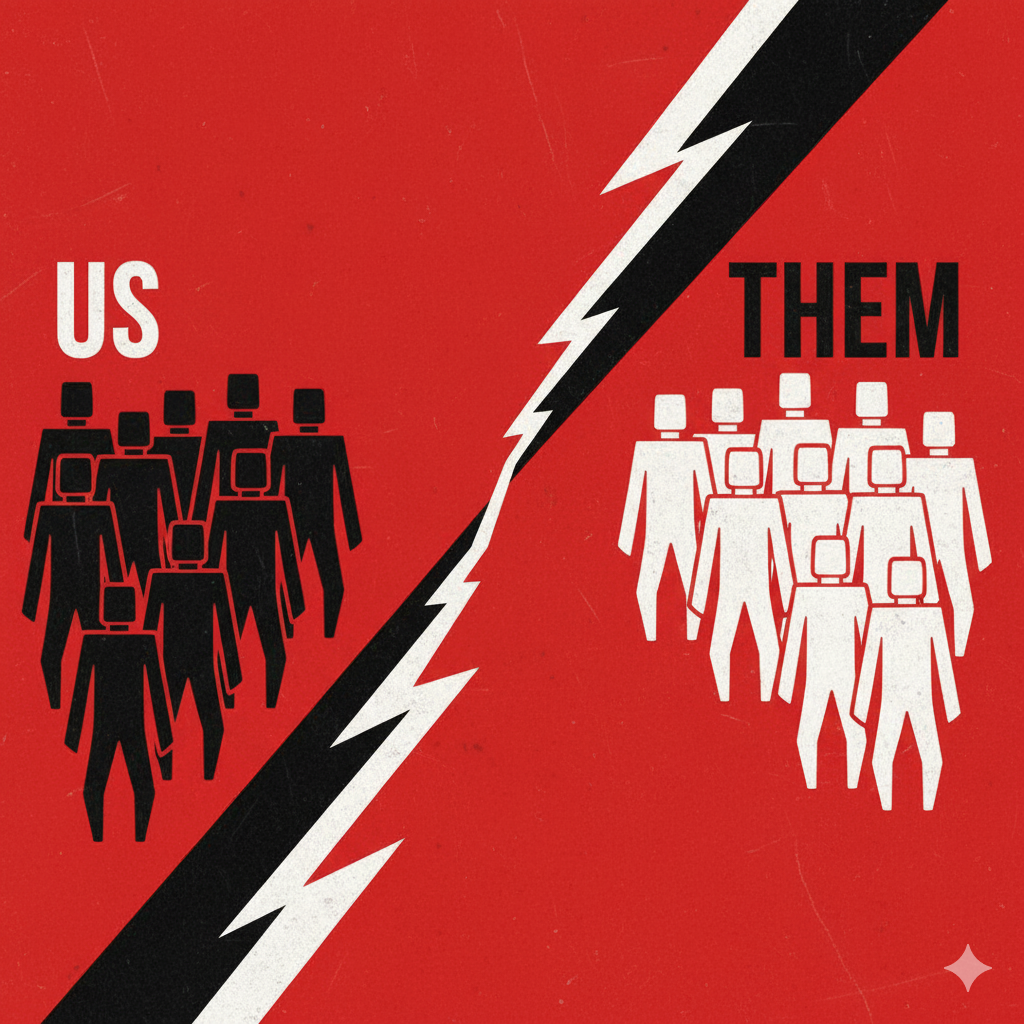

Black and white thinking can also be seen in political or social contexts, where individuals categorize people or groups as either completely good or completely bad, without acknowledging any nuances or complexities. This type of thinking can lead to polarizing beliefs, rigid ideologies, and an unwillingness to engage in constructive dialogue or compromise.

The origins of black and white thinking are complex and multifaceted, but it can stem from a variety of factors, including childhood experiences, cultural and societal influences, and psychological disorders including personality disorder. For example, individuals who have experienced trauma or abuse may engage in black and white thinking as a way to cope with the complexity and ambiguity of their experiences. Similarly, cultural or societal influences that promote a strict adherence to binary categories can also contribute to black and white thinking.

Psychological disorders such as borderline personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and eating disorders are also associated with black and white thinking. For example, individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) may see themselves or others as either completely good or completely bad, without any middle ground. This type of thinking can lead to unstable relationships, impulsive behavior, and emotional dysregulation.

Narcissists too, especially malignant narcissists, tend to exhibit black and white thinking, with the frequent framing of any narrative as being primarily about themselves (good/The Hero) and everyone else (bad/The Other).

Black and White Thinking: Understanding binary cognition in the modern era

The Digital Amplification of Binary Thinking

The modern information ecosystem has created unprecedented conditions for black and white thinking to flourish. Social media algorithms, designed to maximize engagement, systematically promote content that evokes strong emotional responses—often content that presents complex issues in oversimplified, polarizing terms.

Algorithmic Reinforcement Mechanisms

Contemporary digital platforms operate on engagement metrics that inadvertently reward binary thinking:

- Filter Bubble Formation: Recommendation algorithms create echo chambers where users primarily encounter information that confirms their existing beliefs

- Engagement Optimization: Content that provokes outrage or strong agreement receives higher distribution (and ultimately, revenue), marginalizing nuanced perspectives

- Attention Economy Dynamics: The competition for limited attention spans incentivizes simplified, emotionally charged messaging over complex analysis — going straight for the jugular of common mental heuristics works

Information Processing Under Cognitive Load

Research in cognitive psychology demonstrates that when individuals experience high cognitive load—a common state in our information-saturated environment—they default to simplified decision-making heuristics. This neurological tendency combines with digital information delivery systems to create systematic biases toward binary categorization.

Contemporary Political Manifestations

Black and white thinking has become increasingly prominent in political discourse, with profound implications for democratic institutions and social cohesion.

Institutional Polarization Patterns

Recent decades have witnessed unprecedented levels of political polarization across multiple institutional domains:

Legislative Dynamics: Congressional voting patterns show dramatic increases in party-line voting, with bipartisan legislation becoming increasingly rare. This reflects not just strategic positioning but fundamental shifts in how political actors conceptualize policy problems and solutions.

Media Ecosystem Fragmentation: The proliferation of ideologically aligned media sources enables individuals to construct information diets that reinforce binary worldviews. Traditional journalistic ethics of objectivity and balance in a fundamentally evidentiary role have been challenged by partisan media models that explicitly advocate for particular political perspectives.

Electoral Coalition Building: Political campaigns increasingly rely on mobilizing base supporters through appeals to fundamental differences with opponents, rather than building broad coalitions through compromise and incremental policy development.

Identity-Based Political Cognition

Modern political psychology research reveals how black and white thinking intersects with identity formation:

- Social Identity Theory: Individuals derive significant psychological satisfaction from in-group membership and out-group differentiation

- Motivated Reasoning: People process political information in ways that protect their group identities and existing belief systems

- Moral Foundations: Different political coalitions emphasize different moral frameworks, creating seemingly irreconcilable worldview differences

Systemic Analysis: Institutional Impacts

Black and white thinking creates cascade effects across multiple institutional systems:

Democratic Governance Challenges

Compromise Mechanisms: Effective democratic governance requires negotiation and compromise between competing interests. Binary thinking undermines these processes by framing compromise as betrayal of fundamental principles.

Policy Implementation: Complex policy challenges—from healthcare to climate change to economic inequality—require nuanced, multifaceted solutions. Binary thinking promotes oversimplified policy approaches that often fail to address underlying systemic issues.

Constitutional Design: Democratic institutions assume citizens capable of evaluating competing claims and making informed choices. Black and white thinking can undermine these foundational assumptions necessary to making democracy work.

Economic System Implications

Market Dynamics: Binary thinking in economic contexts can create boom-bust cycles, as investors and consumers oscillate between extreme optimism and pessimism without recognizing gradual trends and mixed signals.

Innovation Ecosystems: Complex technological and business model innovation requires tolerance for ambiguity and iterative development. Binary thinking can stifle innovation by demanding immediate, clear success metrics. It turns out that diversity is good to the bottom line, actually.

Labor Relations: Effective workplace dynamics require ongoing negotiation between competing interests. Binary thinking can transform routine workplace disagreements into fundamental conflicts.

Mental Model Frameworks for Analysis

Understanding black and white thinking requires sophisticated analytical frameworks:

The Cognitive Bias Cascade Model

Black and white thinking rarely operates in isolation but typically forms part of broader cognitive bias patterns:

- Confirmation Bias: Seeking information that confirms existing beliefs

- Availability Heuristic: Overweighting easily recalled examples

- Fundamental Attribution Error: Attributing others’ behavior to character rather than circumstances

- Group Attribution Error: Assuming individual group members represent entire groups

Systems Thinking Applications

Effective analysis of black and white thinking requires systems-level perspective:

Feedback Loops: How binary thinking creates self-reinforcing cycles that become increasingly difficult to break

Emergence Properties: How individual cognitive patterns create collective social and political dynamics

Leverage Points: Identifying where interventions might most effectively disrupt binary thinking patterns

Historical Pattern Recognition

Historical analysis reveals recurring patterns in how societies navigate between binary and nuanced thinking:

Crisis Periods: Times of social stress typically increase binary thinking as individuals seek certainty and clear action frameworks

Institutional Adaptation: How democratic institutions evolve mechanisms to manage polarization and maintain governance capacity

Cultural Evolution: How societies develop norms and practices that promote or discourage binary thinking

Contemporary Case Studies

Social Media Discourse Patterns

Analysis of millions of social media posts reveals systematic patterns in how binary thinking spreads:

- Viral Content Characteristics: Posts that go viral disproportionately feature binary framing of complex issues

- Engagement Metrics: Binary content generates higher levels of shares, comments, and emotional reactions

- Network Effects: Binary thinking spreads through social networks more rapidly than nuanced analysis

Political Movement Dynamics

Examination of contemporary political movements reveals how binary thinking shapes organizational development:

Movement Mobilization: Binary framing helps movements build initial coalition support by clarifying friend-enemy distinctions

Strategic Communication: Binary messaging dominates political advertising and fundraising appeals

Coalition Maintenance: Binary thinking can help maintain group cohesion but may limit strategic flexibility

Crisis Response Patterns

Analysis of responses to major crises—from pandemics to economic disruptions to international conflicts—demonstrates how binary thinking affects collective decision-making:

Policy Development: Crisis conditions often promote binary policy choices that may not address underlying complexity

Public Communication: Crisis communication frequently relies on binary framing to motivate public compliance with policy measures

International Relations: Crisis situations can push diplomatic relations toward binary alliance structures

Neurological and Psychological Foundations

Understanding black and white thinking requires examining its neurological and psychological foundations:

Cognitive Processing Systems

System 1 vs System 2 Thinking: Daniel Kahneman’s research demonstrates how automatic, intuitive thinking (System 1) tends toward binary categorization, while deliberative thinking (System 2) enables more nuanced analysis.

Threat Detection Mechanisms: Evolutionary psychology suggests that binary thinking may have adaptive advantages in environments requiring quick threat assessment, but becomes maladaptive in complex modern contexts.

Cognitive Load Theory: When individuals experience high cognitive load, they default to simplified decision-making processes that favor binary categorization.

Developmental Psychology Perspectives

Moral Development Stages: Lawrence Kohlberg’s research on moral development shows how individuals progress from binary moral thinking toward more sophisticated ethical reasoning frameworks.

Identity Formation: Erik Erikson’s work on identity development demonstrates how binary thinking can serve important functions during identity formation periods but may become problematic if it persists into adulthood.

Attachment Theory: Insecure attachment patterns can promote binary thinking about relationships and social situations as defensive mechanisms.

Organizational and Institutional Responses

Educational System Adaptations

Educational institutions increasingly recognize the need to develop students’ capacity for nuanced thinking:

Critical Thinking Curricula: Programs specifically designed to help students recognize and resist binary thinking patterns

Media Literacy: Training students to recognize how information systems promote simplified thinking

Interdisciplinary Approaches: Educational approaches that demonstrate how complex problems require multiple perspectives and methodological approaches

Democratic Institution Reforms

Various proposals aim to reduce the institutional incentives for binary thinking:

Electoral System Design: Ranked-choice voting and other electoral innovations that reward coalition-building over polarization

Deliberative Democracy: Institutional mechanisms that bring citizens together for structured discussion of complex policy issues

Legislative Process Reform: Procedural changes that incentivize negotiation and compromise over partisan positioning

Technology Platform Governance

Growing recognition of how digital platforms shape thinking patterns has led to various reform proposals:

Algorithm Transparency: Requiring platforms to disclose how their algorithms prioritize content

Engagement Metric Alternatives: Developing metrics beyond simple engagement that reward constructive discourse

Digital Literacy: Public education initiatives to help users recognize and resist algorithmic manipulation

Constructive Frameworks for Addressing Binary Thinking

Individual-Level Interventions

Mindfulness Practices: Regular mindfulness meditation has been shown to increase tolerance for ambiguity and reduce automatic binary categorization.

Cognitive Behavioral Techniques: Specific therapeutic approaches for identifying and challenging binary thought patterns.

Exposure to Complexity: Deliberately seeking out information sources and experiences that present complex, nuanced perspectives on important issues.

Perspective-Taking Exercises: Structured practices for understanding how situations appear from multiple viewpoints.

Community-Level Initiatives

Dialogue and Deliberation Programs: Community-based initiatives that bring together people with different perspectives for structured conversation about local issues.

Collaborative Problem-Solving: Community projects that require cooperation across different groups and perspectives.

Civic Education: Educational programs that help citizens understand how democratic institutions work and why compromise is essential for effective governance.

Cross-Cutting Social Connections: Initiatives that help people form relationships across traditional dividing lines.

Institutional Design Principles

Procedural Safeguards: Institutional mechanisms that slow down decision-making processes to allow for more deliberative consideration of complex issues.

Stakeholder Inclusion: Decision-making processes that systematically include multiple perspectives and interests.

Transparency and Accountability: Mechanisms that make decision-making processes visible and subject to public scrutiny.

Adaptive Management: Institutional frameworks that allow for policy adjustment based on evidence and changing circumstances.

Implications for Democratic Resilience

The prevalence of black and white thinking poses significant challenges for democratic governance:

Representation and Legitimacy

Electoral Representation: Binary thinking can undermine representative democracy by making it difficult for elected officials to represent diverse constituencies with complex, sometimes conflicting interests.

Institutional Legitimacy: When citizens view political institutions through binary lenses, it becomes difficult to maintain the shared commitment to democratic norms necessary for effective governance.

Minority Rights: Binary thinking can threaten minority rights by reducing complex questions of individual liberty and collective welfare to simple majority-minority power dynamics.

Policy Development and Implementation

Evidence-Based Policy: Effective policy development requires careful consideration of evidence, trade-offs, and unintended consequences—all of which are undermined by binary thinking.

Policy Adaptation: Democratic institutions must be able to adapt policies based on new evidence and changing circumstances, which requires tolerance for complexity and ambiguity.

Cross-Sector Coordination: Modern policy challenges often require coordination across different levels of government and between public and private sectors, which is complicated by binary thinking.

Future Research Directions

Understanding and addressing black and white thinking requires ongoing research across multiple disciplines:

Technology and Cognition

AI and Decision-Making: How artificial intelligence systems might be designed to promote nuanced rather than binary thinking.

Digital Environment Design: Research on how different digital interface designs affect cognitive processing and decision-making.

Virtual Reality and Perspective-Taking: How immersive technologies might be used to help individuals understand complex situations from multiple perspectives.

Political Psychology and Behavior

Motivation and Binary Thinking: Research on what motivates individuals to adopt or resist binary thinking patterns in political contexts.

Group Dynamics: How binary thinking spreads through social networks and political organizations.

Leadership and Framing: How political leaders can effectively communicate about complex issues without resorting to binary framing.

Institutional Design and Reform

Comparative Democratic Systems: Analysis of how different democratic institutions manage polarization and promote constructive political discourse.

Experimental Governance: Small-scale experiments with different institutional designs that might reduce incentives for binary thinking.

Technology Governance: Research on how to regulate digital platforms in ways that promote constructive rather than polarizing discourse.

Toward cognitive complexity

Black and white thinking represents a fundamental challenge to effective individual decision-making, social cooperation, and democratic governance. While binary thinking may have served adaptive functions in simpler environments, the complexity of modern challenges requires more sophisticated cognitive frameworks.

Addressing this challenge requires coordinated efforts across multiple levels—from individual practices that promote cognitive flexibility to institutional reforms that reduce incentives for polarization. The stakes are particularly high for democratic societies, which depend on citizens’ capacity to engage constructively with complexity and difference.

The path forward requires neither naive optimism nor cynical resignation, but rather sustained commitment to developing our collective capacity for nuanced thinking about complex problems. This involves both protecting democratic institutions from the corrosive effects of extreme polarization and actively building new capabilities for constructive engagement across difference — knowing that some will disagree and continuously fight us on reforms.

Understanding black and white thinking is not merely an academic exercise but an urgent practical necessity for navigating the challenges of the 21st century. By developing more sophisticated analytical frameworks and practical interventions, we can work toward societies that are both more thoughtful and more effective at solving complex collective problems.

Related concepts and further reading

- Cognitive Bias Research: Systematic exploration of how human thinking systematically deviates from logical reasoning

- Political Psychology: Interdisciplinary field examining how psychological processes affect political behavior

- Systems Thinking: Analytical approaches that focus on relationships and patterns rather than isolated events

- Democratic Theory: Normative and empirical research on how democratic institutions work and how they might be improved

- Media Ecology: Study of how communication technologies shape human consciousness and social organization

- Conflict Resolution: Practical approaches for managing disagreement and building cooperation across difference