The Christian nationalist movement has been coalescing itself over the past 50 years (and more), partly in the shadows and partly very publicly through scandals and political strife. This list of Christian nationalism books aims to cover both ends of the spectrum.

Christian nationalism overlaps and shares some common cause with the white nationalism movement and nationalism ideologies more broadly in the US.

Here are some of the best resources I’ve found to navigate the zealous yet fragile world of Christian nationalism, so far:

Christian nationalism books

The Power Worshippers

🔋 The Power Worshippers — Katherine Stewart

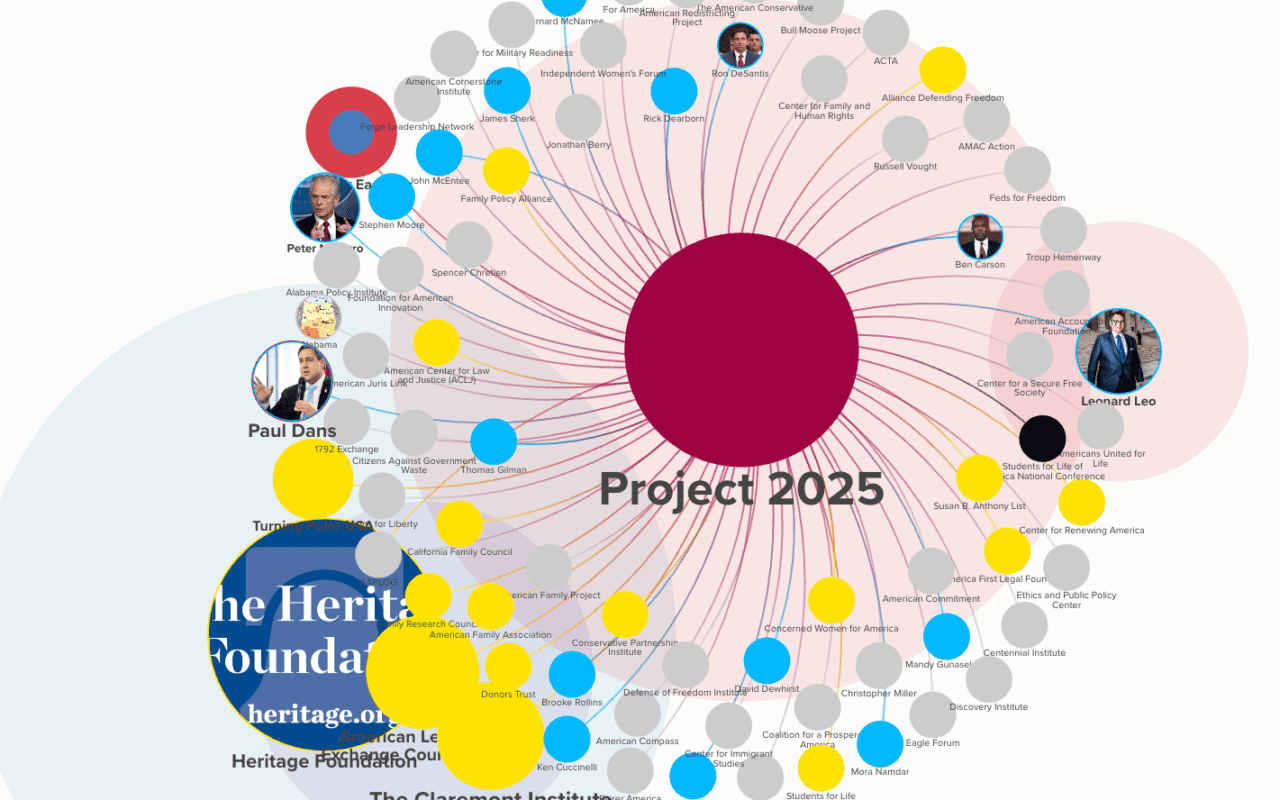

The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism by Katherine Stewart is a comprehensive examination of the growing influence of Christian nationalism in US politics. Stewart delves into the movement’s origins, tracing its development from fringe ideology to a dominant force shaping contemporary policy and societal norms. She uncovers the network of religious leaders, political operatives, and plutocratic donors who are driving this agenda, revealing their strategies to mobilize voters, influence legislation, and reshape the American legal system. Through meticulous research and vivid storytelling, Stewart exposes the ways in which this movement seeks to undermine the separation of church and state, imposing a specific religious worldview on a diverse populace accustomed to enjoying their freedom of religion.

In the book, Stewart highlights how Christian nationalism is not merely a cultural phenomenon but a deliberate, coordinated, and concentrated political effort. She provides detailed accounts of how the movement capitalizes on issues such as abortion, LGBTQ rights, and religious liberty to galvanize support and exert pressure on political leaders. Stewart argues that this agenda poses a significant threat to democratic values and pluralism, advocating for vigilant resistance to protect the integrity of the nation’s secular institutions. By intertwining personal narratives with in-depth analysis, “The Power Worshippers” offers a critical look at the implications of religious nationalism for the future of American democracy.

Unholy

😈 Unholy: How White Christian Nationalists Powered the Trump Presidency, and the Devastating Legacy They Left Behind — Sarah Posner

Unholy: How White Christian Nationalists Powered the Trump Presidency, and the Devastating Legacy They Left Behind by Sarah Posner is an incisive exploration of the alliance between white Christian nationalists and Donald Trump. Posner meticulously documents how this group, driven by a fervent belief in their self-declared divine mandate, played a pivotal role in Trump’s election and subsequent administration. She explores the historical roots of this movement, its theological underpinnings, and the powerful figures who have shaped its direction. Through extensive interviews and detailed reporting, Posner reveals how white Christian nationalists leveraged their significant influence to advance a political agenda that aligns with their religious convictions, often at the expense of democratic norms and minority rights.

Posner’s book delves into the complex relationship between Trump and his evangelical supporters, showing how their mutual needs and ambitions created a symbiotic bond. She illustrates how this unhealthy alliance has led to policies and judicial appointments that reflect the priorities of white Christian nationalists, such as restrictions on reproductive rights, opposition to LGBTQ equality, and the dismantling of church-state separation. “Unholy” also examines the broader cultural impact of this movement, highlighting the ways it has contributed to the polarization and division within American society. Through a blend of investigative journalism and sharp analysis, Posner provides a compelling narrative about the enduring and troubling legacy of this powerful political alliance.

The Immoral Majority

✝️ The Immoral Majority: Why Evangelicals Chose Political Power Over Christian Values — Ben Howe

The Immoral Majority: Why Evangelicals Chose Political Power Over Christian Values by Ben Howe is a critical examination of the evangelical support for Donald Trump and the apparent contradiction between their political choices and their professed Christian values. Howe, an evangelical himself, delves into the reasons why a significant portion of the evangelical community embraced a candidate whose behavior and rhetoric often starkly contrasted with traditional Christian teachings. Through personal anecdotes, interviews, and keen analysis, Howe explores how the pursuit of political power and cultural influence led many evangelicals to compromise on key moral and ethical principles.

In the book, Howe argues that the evangelical community’s alignment with Trump reveals a broader shift within American Christianity, where political expediency has overshadowed the core tenets of the faith. He critically examines how issues such as abortion, religious liberty, and conservative judicial appointments were used to justify unwavering support for Trump, despite his moral failings. Howe also addresses the long-term consequences of this alliance, suggesting that the evangelical movement’s credibility and moral authority have been significantly undermined. “The Immoral Majority” offers a thought-provoking reflection on the intersection of faith and politics, challenging readers to consider the true cost of prioritizing political power over spiritual integrity.

White Evangelical Racism

👻 White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America — Anthea Butler

White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America by Anthea Butler is a compelling exploration of the historical and contemporary intersections between white evangelicalism and racism in the United States. Butler meticulously traces the roots of evangelical racism back to the 19th century, highlighting how racial prejudice and discriminatory practices were often justified through religious rhetoric and beliefs. She examines the ways in which white evangelicals have historically supported segregation, opposed civil rights, and upheld systems of racial inequality, all while professing a commitment to Christian morality.

Butler’s book also delves into the modern political landscape, showing how white evangelical racism has influenced contemporary politics, particularly in the support for Donald Trump. She argues that white evangelicals have frequently prioritized their racial and cultural interests over the inclusive values they claim to uphold. Through a blend of historical analysis and modern political critique, Butler demonstrates how racism has been an enduring element of white evangelical identity and political engagement. “White Evangelical Racism” challenges readers to confront the moral contradictions within the evangelical movement and consider the broader implications for American society and politics.

White Too Long

🏳️ White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity — Robert P. Jones

White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity by Robert P. Jones is a profound examination of the deep-seated connections between white supremacy and American Christianity. Jones, a religious scholar and CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, utilizes historical research, sociological data, and personal reflections to trace the ways in which white Christian churches have perpetuated racial inequality and supported systems of oppression. He argues that white supremacy is not just a historical aberration but a defining characteristic of American Christianity that has shaped its institutions, doctrines, and practices.

In the book, Jones explores how white Christian communities have often resisted racial integration and civil rights, aligning themselves with ideologies that uphold racial hierarchies. He provides a detailed account of how these communities have used theology to justify segregation, discrimination, and violence against people of color. Jones also addresses the contemporary implications of this legacy, urging white Christians to confront and repent for their complicity in racism. By blending personal narrative with rigorous scholarship, “White Too Long” challenges readers to acknowledge the pervasive influence of white supremacy within American Christianity and to seek genuine reconciliation and justice.

Wrapped in the Flag

🇺🇸 Wrapped in the Flag: A Personality History of America’s Radical Right — Claire Conner

Wrapped in the Flag: A Personal History of America’s Radical Right by Claire Conner is a poignant memoir that delves into the rise and influence of the radical right in American politics, with a particular emphasis on its hardline Christian stance. Claire Conner, whose parents were staunch members of the John Birch Society (JBS), provides a deeply personal perspective on how the JBS’s extreme conservative and religious ideologies shaped her upbringing and the broader conservative movement. Through her narrative, Conner exposes the Society’s fervent anti-communism, its use of fear-mongering tactics, and its uncompromising quest for political power, all underpinned by a strict interpretation of Christian values.

In the book, Conner recounts her childhood in a household where the JBS’s radical Christian beliefs were not only embraced but fervently promoted. She explores how these beliefs drove the Society’s opposition to civil rights, its promotion of segregation, and its rejection of any form of progressive social change. Conner reflects on the broader implications of this hardline stance, showing how the JBS’s combination of political extremism and religious zealotry influenced the modern conservative movement. “Wrapped in the Flag” serves as both a personal memoir and a critical historical analysis, offering readers an insightful look at the roots of America’s radical right and its enduring impact on contemporary politics, especially through its integration of rigid Christian ideology.

One Nation Under God

📈 One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America — Kevin M. Kruse

One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America by Kevin M. Kruse is an insightful exploration of the strategic alliance between corporate America and religious leaders to promote a Christian identity for the nation. Kruse meticulously traces the origins of this partnership back to the mid-20th century, revealing how business leaders and conservative politicians collaborated with prominent clergy to counter the New Deal and the growing influence of secularism. By championing the idea that America was founded as a Christian nation, they sought to foster a moral framework that aligned with free-market capitalism and conservative political values.

Kruse’s book delves into how this orchestrated campaign reshaped American public life, embedding religious language and symbols into the political and cultural fabric of the nation. He details how corporate-funded initiatives popularized practices such as adding “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance and “In God We Trust” on currency, effectively merging religious faith with national identity. Through a combination of historical research and engaging narrative, “One Nation Under God” uncovers the deliberate efforts to create a Christian America from whole cloth, highlighting the lasting impact of this movement on contemporary politics and society. Kruse’s work challenges readers to reconsider the origins of America’s religious rhetoric and its potentially dangerous implications for the nation’s democratic principles.

The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory

⛪ The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism — Tim Alberta

The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism by Tim Alberta is a penetrating examination of the evolving role of evangelicals in American politics, particularly in the context of rising extremism. Alberta, a seasoned political journalist and former Evangelical, provides a comprehensive analysis of how the evangelical movement has increasingly aligned itself with radical political ideologies, often prioritizing political power over traditional Christian values. He explores the complex dynamics within the evangelical community, highlighting the tensions between maintaining religious integrity and engaging in partisan battles.

Alberta’s book offers a detailed account of key events and figures that have shaped the current evangelical landscape, from the Moral Majority and the rise of the religious right to the influence of prominent evangelical leaders in the Trump era. He delves into the ways in which evangelicals have embraced extreme positions on issues such as immigration, LGBTQ rights, and religious liberty, often at odds with the inclusive message of Christianity. Through rigorous reporting and insightful commentary, “The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory” challenges readers to understand the deep-rooted factors driving evangelical political engagement and the implications for American democracy. Alberta’s work provides a critical perspective on the intersection of faith and politics in an age of increasing polarization and extremism.