Stochastic terrorism is a term that has emerged in the lexicon of political and social analysis to describe a method of inciting violence indirectly through the use of mass communication. This concept is predicated on the principle that while not everyone in an audience will act on violent rhetoric, a small percentage might.

The term “stochastic” refers to a process that is randomly determined; it implies that the specific outcomes are unpredictable, yet the overall distribution of these outcomes follows a pattern that can be statistically analyzed. In the context of stochastic terrorism, it means that while it is uncertain who will act on incendiary messages and violent political rhetoric, it is almost certain that someone will.

The nature of stochastic terrorism

Stochastic terrorism involves the dissemination of public statements, whether through speeches, social media, or traditional media, that incite violence. The individuals or entities spreading such rhetoric may not directly call for political violence. Instead, they create an atmosphere charged with tension and hostility, suggesting that action must be taken against a perceived threat or enemy. This indirect incitement provides plausible deniability, as those who broadcast the messages can claim they never explicitly advocated for violence.

Prominent stochastic terrorism examples

The following are just a few notable illustrative examples of stochastic terrorism:

- The Oklahoma City Bombing (1995): Timothy McVeigh, influenced by extremist anti-government rhetoric, the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff, and the 1993 siege at Waco, Texas, detonated a truck bomb outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people. This act was fueled by ideologies that demonized the federal government, highlighting how extremism and extremist propaganda can inspire individuals to commit acts of terror.

- The Oslo and Utøya Attacks (2011): Anders Behring Breivik, driven by anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant beliefs, bombed government buildings in Oslo, Norway, then shot and killed 69 people at a youth camp on the island of Utøya. Breivik’s manifesto cited many sources that painted Islam and multiculturalism as existential threats to Europe, showing the deadly impact of extremist online echo chambers and the pathology of right-wing ideologies such as Great Replacement Theory.

- The Pittsburgh Synagogue Shooting (2018): Robert Bowers, influenced by white supremacist ideologies and conspiracy theories about migrant caravans, killed 11 worshippers in a synagogue. His actions were preceded by social media posts that echoed hate speech and conspiracy theories rampant in certain online communities, demonstrating the lethal consequences of unmoderated hateful rhetoric.

- The El Paso Shooting (2019): Patrick Crusius targeted a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, killing 23 people, motivated by anti-immigrant sentiment and rhetoric about a “Hispanic invasion” of Texas. His manifesto mirrored language used in certain media and political discourse, underscoring the danger of using dehumanizing language against minority groups.

- Christchurch Mosque Shootings (2019): Brenton Tarrant live-streamed his attack on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 51 people, influenced by white supremacist beliefs and online forums that amplified Islamophobic rhetoric. The attacker’s manifesto and online activity were steeped in extremist content, illustrating the role of internet subcultures in radicalizing individuals.

Stochastic terrorism in right-wing politics in the US

In the United States, the concept of stochastic terrorism has become increasingly relevant in analyzing the tactics employed by certain right-wing entities and individuals. While the phenomenon is not exclusive to any single political spectrum, recent years have seen notable instances where right-wing rhetoric has been linked to acts of violence.

The January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol serves as a stark example of stochastic terrorism. The event was preceded by months of unfounded claims of electoral fraud and calls to “stop the steal,” amplified by right-wing media outlets and figures — including then-President Trump who had extraordinary motivation to portray his 2020 election loss as a victory in order to stay in power. This rhetoric created a charged environment, leading some individuals to believe that violent action was a justified response to defend democracy.

The role of media and technology

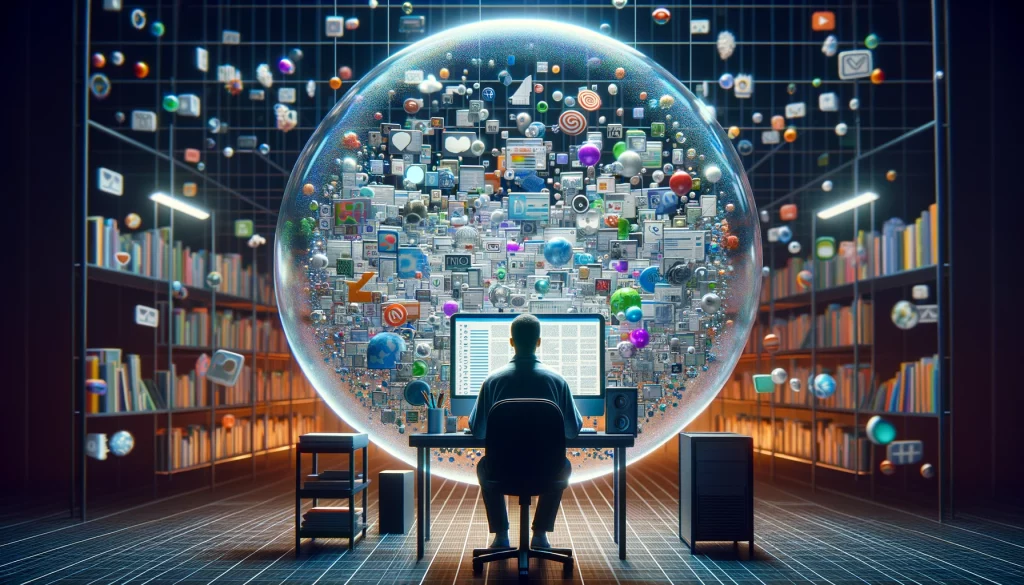

Right-wing media platforms have played a significant role in amplifying messages that could potentially incite stochastic terrorism. Through the strategic use of incendiary language, disinformation, misinformation, and conspiracy theories, these platforms have the power to reach vast audiences and influence susceptible individuals to commit acts of violence.

The advent of social media has further complicated the landscape, enabling the rapid spread of extremist rhetoric. The decentralized nature of these platforms allows for the creation of echo chambers where inflammatory messages are not only amplified but also go unchallenged, increasing the risk of radicalization.

Challenges and implications

Stochastic terrorism presents significant legal and societal challenges. The indirect nature of incitement complicates efforts to hold individuals accountable for the violence that their rhetoric may inspire. Moreover, the phenomenon raises critical questions about the balance between free speech and the prevention of violence, challenging societies to find ways to protect democratic values while preventing harm.

Moving forward

Addressing stochastic terrorism requires a multifaceted approach. This includes promoting responsible speech among public figures, enhancing critical thinking and media literacy among the public, and developing legal and regulatory frameworks that can effectively address the unique challenges posed by this form of terrorism. Ultimately, combating stochastic terrorism is not just about preventing violence; it’s about preserving the integrity of democratic societies and ensuring that public discourse does not become a catalyst for harm.

Understanding and mitigating the effects of stochastic terrorism is crucial in today’s increasingly polarized world. By recognizing the patterns and mechanisms through which violence is indirectly incited, societies can work towards more cohesive and peaceful discourse, ensuring that democracy is protected from the forces that seek to undermine it through fear and division.